Hernias occur when there is a weak point in a cavity wall, usually affecting the muscle or fascia. This weakness allows a body organ (e.g., bowel) that would normally be contained within that cavity to pass through the cavity wall.

Presentation

There are many types of hernias that present differently depending on where they are and what organs are involved.

The typical features of an abdominal wall hernia are:

- A soft lump protruding from the abdominal wall

- The lump may be reducible (it can be pushed back into the normal place)

- The lump may protrude on coughing (raising intra-abdominal pressure) or standing (pulled out by gravity)

- Aching, pulling or dragging sensation

Complications

There are three key complications of hernias:

- Incarceration

- Obstruction

- Strangulation

Incarceration is where the hernia cannot be reduced back into the proper position (it is irreducible). The bowel is trapped in the herniated position. Incarceration can lead to obstruction and strangulation of the hernia.

Obstruction is where a hernia causes a blockage in the passage of faeces through the bowel. Obstruction presents with vomiting, generalised abdominal pain and absolute constipation (not passing faeces or flatus).

Strangulation is where a hernia is non-reducible (it is trapped with the bowel protruding) and the base of the hernia becomes so tight that it cuts off the blood supply, causing ischaemia. This will present with significant pain and tenderness at the hernia site. Strangulation is a surgical emergency. The bowel will die quickly (within hours) if not corrected with surgery. There will also be a mechanical obstruction when this occurs.

TOM TIP: Hernias that have a wide neck, meaning that the size of the opening that allows abdominal contents through is large, are at lower risk of complications. While the contents can easily pass out of this opening, they can also easily be put back, which puts them at a lower risk of incarceration, obstruction and strangulation. When assessing a hernia, always comment on the size of the neck/defect (narrow or wide), as this will help formulate a risk assessment and management plan for the hernia (such as how urgently they need to be operated on).

Richter’s Hernia

A Richter’s hernia is a very specific situation that can occur in any abdominal hernia. This is where only part of the bowel wall and lumen herniate through the defect, with the other side of that section of the bowel remaining within the peritoneal cavity. They can become strangulated, where the blood supply to that portion of the bowel wall is constricted and cut off. Strangulated Richter’s hernias will progress very rapidly to ischaemia and necrosis and should be operated on immediately.

Maydl’s Hernia

Maydl’s hernia refers to a specific situation where two different loops of bowel are contained within the hernia.

General Management Options

There are general principles of management that apply to abdominal wall hernias. These are:

- Conservative management

- Tension-free repair (surgery)

- Tension repair (surgery)

Conservative management involves leaving the hernia alone. This is most appropriate when the hernia has a wide neck (low risk of complications) and in patients that are not good candidates for surgery due to co-morbidities.

Tension-free repair involves placing a mesh over the defect in the abdominal wall. The mesh is sutured to the muscles and tissues on either side of the defect, covering it and preventing herniation of the cavity contents. Over time, tissues grow into the mesh and provide extra support. This has a lower recurrence rate compared with tension repair, but there may be complications associated with the mesh (e.g., chronic pain).

Tension repair involves a surgical operation to suture the muscles and tissue on either side of the defect back together. Tension repairs are rarely performed and have been largely replaced by tension-free repairs. The hernia is held closed (to heal there) by sutures applying tension. This can cause pain and there is a relatively high recurrence rate of the hernia.

Inguinal Hernias

Inguinal hernias present with a soft lump in the inguinal region (in the groin). There are two types:

- Indirect inguinal hernia

- Direct inguinal hernia

There are a number of differential diagnoses for a lump in the inguinal region:

- Femoral hernia

- Lymph node

- Saphena varix (dilation of saphenous vein at junction with femoral vein in groin)

- Femoral aneurysm

- Abscess

- Undescended / ectopic testes

- Kidney transplant

Indirect Inguinal Hernia

An indirect inguinal hernia is where the bowel herniates through the inguinal canal.

The inguinal canal is a tube that runs between the deep inguinal ring (where it connects to the peritoneal cavity), and the superficial inguinal ring (where it connects to the scrotum).

In males, the inguinal canal is what allows the spermatic cord and its contents to travel from inside the peritoneal cavity, through the abdominal wall and into the scrotum.

In females, the round ligament is attaches to the uterus and passes through the deep inguinal ring, inguinal canal and then attaches to the labia majora.

During fetal development, the processus vaginalis is a pouch of peritoneum that extends from the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal. This allows the testes to descend from the abdominal cavity, through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. Normally, after the testes descend through the inguinal canal, the deep inguinal ring closes and the processus vaginalis is obliterated. However, in some patients, the inguinal ring remains patent, and the processus vaginalis remains intact. This leaves a tract or tunnel from the abdominal contents, through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. The bowel can herniate along this tract, creating an indirect inguinal hernia.

There is a specific finding of indirect inguinal hernias that help you differentiate them from a direct inguinal hernias. When an indirect hernia is reduced and pressure is applied (with two fingertips) to the deep inguinal ring (at the mid-way point from the ASIS to the pubic tubercle), the hernia will remain reduced.

Direct Inguinal Hernia

Direct inguinal hernias occur due to weakness in the abdominal wall at Hesselbach’s triangle. The hernia protrudes directly through the abdominal wall, through Hesselbach’s triangle (not along a canal or tract like an indirect inguinal hernia). Pressure over the deep inguinal ring will not stop the herniation.

Hesselbach’s triangle boundaries (RIP mnemonic):

- R – Rectus abdominis muscle – medial border

- I – Inferior epigastric vessels – superior / lateral border

- P – Poupart’s ligament (inguinal ligament) – inferior border

Femoral Hernias

Femoral hernias involve herniation of the abdominal contents through the femoral canal. This occurs below the inguinal ligament, at the top of the thigh.

The opening between the peritoneal cavity and the femoral canal is the femoral ring. The femoral ring leaves only a narrow opening for femoral hernias, putting femoral hernias at high risk of:

- Incarceration

- Obstruction

- Strangulation

Boundaries of the femoral canal (FLIP mnemonic):

- F – Femoral vein laterally

- L – Lacunar ligament medially

- I – Inguinal ligament anteriorly

- P – Pectineal ligament posteriorly

Don’t get the femoral canal confused with the femoral triangle. The femoral triangle is a larger area at the top of the thigh that contains the femoral canal. You can remember the boundaries with the SAIL mnemonic:

- S – Sartorius – lateral border

- A – Adductor longus – medial border

- IL – Inguinal Ligament – superior border

Use the NAVY-C mnemonic to remember the contents of the femoral triangle from lateral to medial across the top of the thigh:

- N – Femoral Nerve

- A – Femoral Artery

- V – Femoral Vein

- Y – Y-fronts

- C – Femoral Canal (containing lymphatic vessels and nodes)

Incisional Hernias

Incisional hernias occur at the site of an incision from previous surgery. They are due to weakness where the muscles and tissues were closed after a surgical incision. The bigger the incision, the higher the risk of a hernia forming. Medical co-morbidities put patients at higher risk due to poor healing.

Incisional hernias can be difficult to repair, with a high rate of recurrence. They are often left alone if they are large, with a wide neck and low risk of complications, particularly in patients with multiple co-morbidities.

Umbilical Hernias

Umbilical hernias occur around the umbilicus due to a defect in the muscle around the umbilicus.

Umbilical hernias are common in neonates and can resolve spontaneously. They can also occur in older adults.

Epigastric Hernias

An epigastric hernia is simply a hernia in the epigastric area (upper abdomen).

Spigelian Hernias

A Spigelian hernia occurs between the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle and the linea semilunaris. This is the site of the spigelian fascia, which is an aponeurosis between the muscles of the abdominal wall. Usually, this occurs in the lower abdomen and may present with non-specific abdominal wall pain. There may not be a noticeable lump.

An ultrasound scan can help establish the diagnosis.

Spigelian hernias generally have a narrower base, increasing the risk of incarceration, obstruction and strangulation.

Diastasis Recti

Diastasis recti may also be called rectus diastasis and recti divarication. It refers to a widening of the linea alba, the connective tissue that separates the rectus abdominis muscle, forming a larger gap between the rectus muscles. It is not technically a hernia. This gap becomes most prominent when the patient lies on their back and lifts their head. There is a protruding bulge along the middle of the abdomen.

The linea alba is the aponeurosis of the two sides of the rectus abdominis muscle. The gap is created because the linea alba is stretched and broad.

This can be congenital (in newborns) or due to weakness in the connective tissue, for example following pregnancy or in obese patients.

No treatment is required in most cases, but surgical repair is possible.

Obturator Hernias

Obturator hernias are where the abdominal or pelvic contents herniate through the obturator foramen at the bottom of the pelvis. They occur due to a defect in the pelvic floor and are more common in women, particularly in older age, after multiple pregnancies and vaginal deliveries. They are often asymptomatic but may present with irritation to the obturator nerve, causing pain in the groin or medial thigh.

Howship–Romberg sign refers to pain extending from the inner thigh to the knee when the hip is internally rotated and is due to compression of the obturator nerve.

It can also present with complications of:

- Incarceration

- Obstruction

- Strangulation

CT or MRI of the pelvis can establish the diagnosis. It may be found incidentally during pelvic surgery.

Hiatus Hernias

An hiatus hernia refers to the herniation of the stomach up through the diaphragm. The diaphragm opening should be at the level of the lower oesophageal sphincter and should be fixed in place. A narrow opening helps to maintain the sphincter and stop acid and stomach contents refluxing into the oesophagus. When the opening of the diaphragm is wider, the stomach can enter through the diaphragm and the contents of the stomach can reflux into the oesophagus.

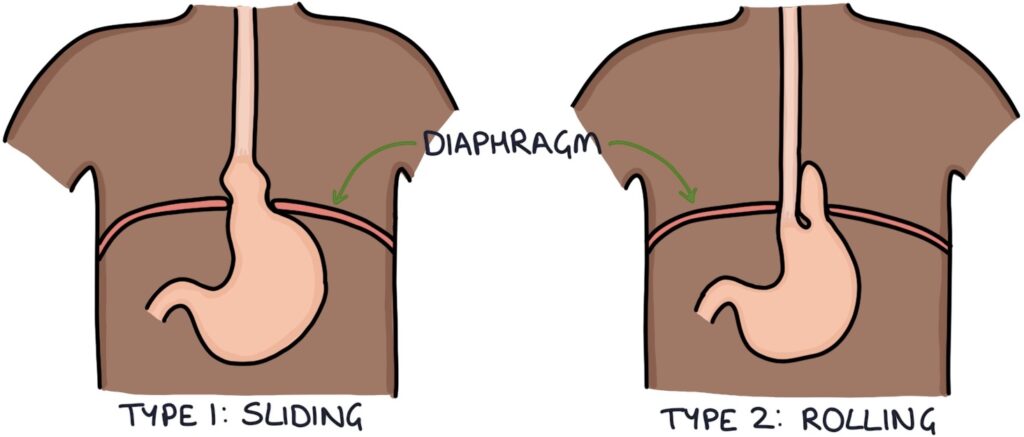

There are four types of hiatus hernia:

- Type 1: Sliding

- Type 2: Rolling

- Type 3: Combination of sliding and rolling

- Type 4: Large opening with additional abdominal organs entering the thorax

Sliding hiatus hernia is where the stomach slides up through the diaphragm, with the gastro-oesophageal junction passing up into the thorax.

Rolling hiatus hernia is where a separate portion of the stomach (i.e. the fundus), folds around and enters through the diaphragm opening, alongside the oesophagus

Type 4 refers to a large hernia that allows other intra-abdominal organs to pass through the diaphragm opening (e.g., bowel, pancreas or omentum).

Key risk factors are increasing age, obesity and pregnancy.

Hiatus hernias present with dyspepsia (indigestion), with symptoms of:

- Heartburn

- Acid reflux

- Reflux of food

- Burping

- Bloating

- Halitosis (bad breath)

Hiatus hernias can be intermittent, meaning they may not be seen on investigations. Hiatus hernias may be seen on:

- Chest x-rays

- CT scans

- Endoscopy

- Barium swallow testing

Treatment is either:

- Conservative (with medical treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux)

- Surgical repair if there is a high risk of complications or symptoms are resistant to medical treatment

Surgery involves laparoscopic fundoplication. This involves tying the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophagus to narrow the lower oesophageal sphincter.

Last updated May 2021

Now, head over to members.zerotofinals.com and test your knowledge of this content. Testing yourself helps identify what you missed and strengthens your understanding and retention.