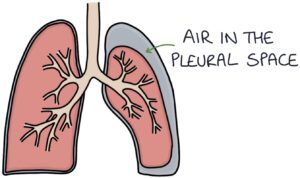

Pneumothorax occurs when air gets into the pleural space, separating the lung from the chest wall. It can occur spontaneously, or secondary to trauma, medical interventions (“iatrogenic”) or lung pathology. The typical patient in exams is a tall, thin young man presenting with sudden breathlessness and pleuritic chest pain, possibly whilst playing sports.

Causes

- Spontaneous

- Trauma

- Iatrogenic, for example, due to lung biopsy, mechanical ventilation or central line insertion

- Lung pathologies such as infection, asthma or COPD

Investigations

An erect chest x-ray is the investigation of choice for a simple pneumothorax.

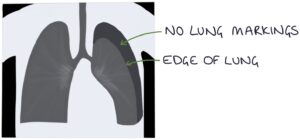

It shows an area between the lung tissue and the chest wall where there are no lung markings. There will be a line demarcating the edge of the lung where the lung markings end and the pneumothorax begins.

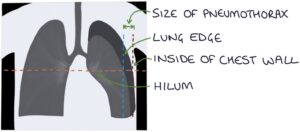

Measuring the size of the pneumothorax on a chest x-ray can be done according to the BTS guidelines from 2010. This involves measuring horizontally from the lung edge to the inside of the chest wall at the level of the hilum.

CT thorax can detect a pneumothorax that is too small to see on a chest x-ray. It can also be used to accurately assess the size of the pneumothorax.

Management

The acute management here is based on the 2010 guidelines from the British Thoracic Society. Always check the latest local and national guidelines, and consult with seniors when managing patients.

No shortness of breath and less than a 2cm rim of air on the chest x-ray:

- No treatment is required as it will spontaneously resolve

- Follow up in 2 – 4 weeks is recommended

Shortness of breath and/or more than a 2cm rim of air on the chest x-ray:

- Aspiration followed by reassessment

- When aspiration fails twice, a chest drain is required

Unstable patients, bilateral or secondary pneumothoraces generally require a chest drain.

Chest Drain

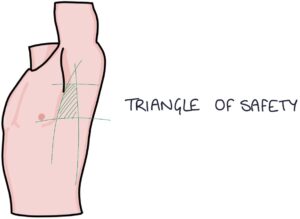

Chest drains can be inserted in the emergency department or on the ward. They are inserted in the “triangle of safety”. This triangle is formed by:

- The 5th intercostal space (or the inferior nipple line)

- The midaxillary line (or the lateral edge of the latissimus dorsi)

- The anterior axillary line (or the lateral edge of the pectoralis major)

The needle is inserted just above the rib to avoid the neurovascular bundle that runs just below the rib. Once the chest drain is inserted, obtain a chest x-ray to check the positioning.

The external end of the drain is placed underwater, creating a seal to prevent air from flowing back through the drain, into the chest. Air can exit the chest cavity and bubble through the water, but the water prevents air from re-entering the drain and chest. During normal respiration, the water in the drain will rise and fall due to changes in pressure in the chest (described as “swinging”).

When the chest drain is successfully treating the pneumothorax, air will bubble through the fluid in the drain bottle. There will be swinging of the water with respiration. On a repeat chest x-ray there will be re-inflation of the lung. If these things do not occur, there may be a problem with the drain, such as:

- Blocked or kinked tube

- Incorrect position in the chest

- Not properly connected to the bottle

Once the pneumothorax resolves, there should be no further bubbling in the drain bottle. The swinging of the water with respiration will also reduce.

Two key complications of chest drains are:

- Air leaks around the drain site (indicated by persistent bubbling of fluid, particularly on coughing)

- Surgical emphysema (also known as subcutaneous emphysema) is when air collects in the subcutaneous tissue

Surgical Management

Patients may require surgical interventions when:

- A chest drain fails to correct the pneumothorax

- There is a persistent air leak in the drain

- The pneumothorax reoccurs (recurrent pneumothorax)

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) can be used to correct the pneumothorax.

The surgical options are:

- Abrasive pleurodesis (using direct physical irritation of the pleura)

- Chemical pleurodesis (using chemicals, such as talc powder, to irritate the pleura)

- Pleurectomy (removal of the pleura)

Pleurodesis involves creating an inflammatory reaction in the pleural lining so that the pleura stick together and the pleural space becomes sealed. This prevents further pneumothoraces from developing.

Tension Pneumothorax

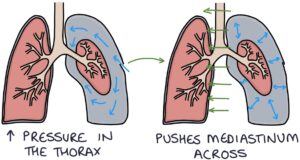

Tension pneumothorax is caused by trauma to the chest wall that creates a one-way valve that lets air in but not out of the pleural space. The one-way valve means that during inspiration air is drawn into the pleural space and during expiration, the air is trapped in the pleural space. Therefore, more air keeps getting drawn into the pleural space with each breath and cannot escape. This is dangerous as it creates pressure inside the thorax that will push the mediastinum across, kink the big vessels in the mediastinum and cause cardiorespiratory arrest.

Signs of Tension Pneumothorax

- Tracheal deviation away from side of the pneumothorax

- Reduced air entry on the affected side

- Increased resonance to percussion on the affected side

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

Management of Tension Pneumothorax

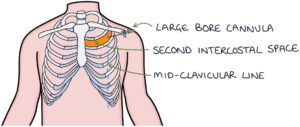

The management sentence you need to learn and recite in your exams is: “Insert a large bore cannula into the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line.”

However, the Advanced Traumatic Life Support (ATLS) recommendations from 2018 recommend for adults, using the “fourth or fifth intercostal space, anterior to the midaxillary axillary line”. The reason for choosing this is this site is that the chest wall thickness may be smaller than in the second intercostal space.

If a tension pneumothorax is suspected, do not wait for any investigations. Once the pressure is relieved with a cannula then a chest drain is required for definitive management.

Last updated May 2021

Now, head over to members.zerotofinals.com and test your knowledge of this content. Testing yourself helps identify what you missed and strengthens your understanding and retention.