Several congenital heart defects may present for the first time, or worsen, in adulthood. The conditions covered here are:

- Atrial septal defects

- Ventricular septal defects

- Coarctation of the aorta

Other congenital heart conditions usually present and are managed in infancy or childhood. They require follow up and monitoring, but the defect is usually repaired by adulthood. These are discussed elsewhere in the paediatrics content:

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Tetralogy of Fallot

- Ebstein’s anomaly

- Transposition of the great arteries

An echocardiogram is the initial investigation of choice for diagnosing congenital heart defects.

Cyanotic Heart Disease

Congenital heart disease can be divided into two categories: cyanotic and acyanotic.

Cyanosis occurs when deoxygenated blood enters the systemic circulation. Cyanotic heart disease occurs when blood can bypass the pulmonary circulation and the lungs. This occurs across a right-to-left shunt. A right-to-left shunt describes any defect that allows blood to flow from the right side of the heart (the deoxygenated blood returning from the body) to the left side of the heart (the blood exiting the heart into the systemic circulation), without travelling through the lungs to get oxygenated.

Heart defects that can cause a right-to-left shunt, and therefore cyanotic heart disease, are:

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

- Atrial septal defect (ASD)

- Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

- Transposition of the great arteries

Patients with a VSD, ASD or PDA are usually not cyanotic. This is because the pressure in the left side of the heart is much greater than the right side, and blood will flow from the area of high pressure to the area of low pressure (left to right). This prevents a right-to-left shunt. If the pulmonary pressure increases beyond the systemic pressure, blood will start to flow from right to left across the defect, causing cyanosis. This is called Eisenmenger syndrome.

Complications

The key complications of congenital heart disease are:

- Heart failure

- Arrhythmias

- Endocarditis

- Stroke

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Eisenmenger Syndrome

Generally, the risks associated with congenital heart defects are much higher during pregnancy. Women with congenital heart defects need to be counselled by their specialist about the risks of pregnancy and require careful monitoring throughout pregnancy.

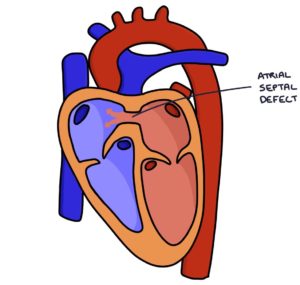

Atrial Septal Defects

An atrial septal defect is a defect (a hole) in the septum (the wall) between the two atria. This connects the right and left atria allowing blood to flow between them.

The types of atrial septal defect, from most to least common, are:

- Patent foramen ovale, where the foramen ovale fails to close (although this is not strictly classified as an ASD)

- Ostium secondum, where the septum secondum fails to fully close, leaving a hole in the wall

- Ostium primum, where the septum primum fails to fully close, leaving a hole in the wall (this tends to lead to a atrioventricular septal defect)

An atrial septal defect leads to a shunt, with blood moving between the two atria. Blood moves from the left atrium to the right atrium because the pressure in the left atrium is higher than the pressure in the right atrium. This means blood continues to flow to the pulmonary vessels and lungs to get oxygenated and the patient does not become cyanotic. However, the increased flow to the right side of the heart leads to right-sided overload and right heart strain. This right-sided overload can lead to right heart failure and pulmonary hypertension.

Eventually, pulmonary hypertension can lead to Eisenmenger syndrome. This occurs because the pulmonary pressure exceeds the systemic pressure, causing the shunt to reverse and become a right-to-left shunt across the ASD. This causes blood to bypass the lungs, resulting in the patient becoming cyanotic.

Presentation of Atrial Septal Defects

Atrial septal defects are often picked up on antenatal scans or newborn examinations. It may be asymptomatic in childhood and present in adulthood with:

- Dyspnoea (shortness of breath) secondary to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure

- Stroke in the context of venous thromboembolism (see below)

- Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter

TOM TIP: It is worth remembering atrial septal defects as a cause of stroke in patients with a DVT. Normally, when patients have a DVT and this becomes an embolus, the clot travels to the right side of the heart, enters the lungs and becomes a pulmonary embolism. In patients with an ASD the clot can travel from the right atrium to the left atrium across the ASD. This means the clot can travel to the left ventricle, aorta and up to the brain, causing a large stroke. An exam question may feature a patient with a DVT that develops a large stroke and the challenge is to identify that they have had a lifelong asymptomatic ASD.

Atrial septal defects cause a mid-systolic, crescendo-decrescendo murmur loudest at the upper left sternal border, with a fixed split second heart sound. Splitting of the second heart sound can be normal with inspiration. However, a “fixed split” second heart sound means the split does not change with inspiration and expiration. This occurs in an atrial septal defect because blood is flowing from the left atrium into the right atrium across the atrial septal defect, increasing the volume of blood that the right ventricle has to empty before the pulmonary valve can close. This doesn’t vary with respiration.

Interestingly, there is a possible link between migraine with aura and patent foramen ovale (PFO). However, patients with migraines are not routinely screened for PFO. This is because the surgical management of PFOs carry risks and it is not clear whether treatment for a PFO improves symptoms of recurrent migraines.

Management of Atrial Septal Defects

In cases where the ASD is small and asymptomatic, watching and waiting may be appropriate. ASDs can be corrected surgically using a percutaneous transvenous catheter closure (via the femoral vein) or open-heart surgery. Anticoagulants (such as aspirin, warfarin and DOACs) are used to reduce the risk of clots and stroke in adults.

Ventricular Septal Defects

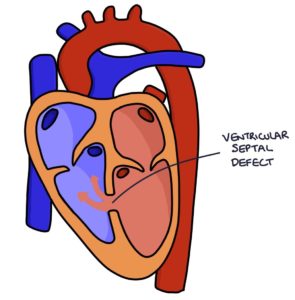

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the septum (wall) between the two ventricles. This can vary in size from tiny to the entire septum, forming one large ventricle.

Congenital VSDs can occur in isolation but there are often underlying genetic conditions associated with them (e.g., Down’s Syndrome and Turner’s Syndrome).

Ventricular septal defects can also develop after myocardial infarction, where there is damage to the ventricular septum due to ischaemia.

Similarly to atrial septal defects, VSDs usually feature a left-to-right shunt. Over time this causes right-sided overload, right heart failure and increased flow into the pulmonary vessels. Pulmonary hypertension may progress to a right-to-left shunt, resulting in cyanosis (Eisenmenger syndrome).

Presentation of Ventricular Septal Defects

Often VSDs are initially asymptomatic and patients can present as late as adulthood. They may be picked up on antenatal scans or when a murmur is heard during the newborn baby check.

Patients with a VSD typically have a pan-systolic murmur more prominently heard at the left lower sternal border in the third and fourth intercostal spaces. There may be a systolic thrill on palpation.

TOM TIP: When you hear a pan-systolic murmur it is worth giving your top differential but also mentioning the other causes of this type of murmur. The causes of a pan-systolic murmur are ventricular septal defect, mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation.

Management of Ventricular Septal Defects

VSDs can be corrected surgically using a transvenous catheter closure via the femoral vein or open-heart surgery.

There is an increased risk of infective endocarditis in patients with a VSD. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered during surgical procedures to reduce the risk of developing infective endocarditis.

Coarctation of the Aorta

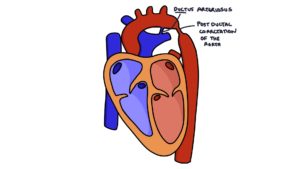

Coarctation of the aorta is a congenital condition where there is a narrowing of the aortic arch, usually around the ductus arteriosus. The severity of the coarctation (or narrowing) can vary from mild to severe. It is often associated with an underlying genetic condition, particularly Turner’s syndrome.

Coarctation of the aorta can reoccur later after previously being treated in childhood.

Narrowing of the aorta reduces the pressure of blood flowing to the arteries that are distal to the narrowing. It increases the pressure in areas proximal to the narrowing, such as the heart and the three branches of the aorta arch (the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid and the left subclavian artery).

Presentation of Coarctation of the Aorta

Coarctation may go undiagnosed until adulthood. Often the first sign in adulthood is hypertension.

There may be a systolic murmur heard below the left clavicle (left infraclavicular area) and below the left scapula.

Performing a four limb blood pressure will reveal high blood pressure in the limbs supplied from arteries that branch off the aorta before the narrowing and lower blood pressure in limbs that branch off the aorta after the narrowing.

Additional signs may develop over time:

- Left ventricular heave due to left ventricular hypertrophy

- Underdeveloped left arm where there is reduced flow to the left subclavian artery

- Underdevelopment of the legs

CT angiography gives a detailed picture of the structure and narrowing in coarctation of the aorta.

Management of Coarctation of the Aorta

The severity of the coarctation varies between patients. In mild cases, patients can live symptom-free until adulthood without requiring surgical input. In severe cases, patients will require emergency surgery shortly after birth.

In adulthood it can be treated with:

- Percutaneous balloon angioplasty (stretching the stenosis), potentially with a stent inserted

- Open surgical repair

Patients also need medical management of hypertension.

Last updated May 2021

Now, head over to members.zerotofinals.com and test your knowledge of this content. Testing yourself helps identify what you missed and strengthens your understanding and retention.