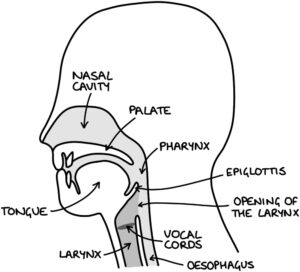

Basic Upper Airway Anatomy

Endotracheal Intubation

An endotracheal tube (ETT) is a flexible plastic tube with an inflatable cuff (balloon) at one end and a connector at the other. The tip of the endotracheal tube is inserted through the mouth, throat (pharynx), larynx and vocal cords into the trachea. Endotracheal tubes come in different sizes, with the diameter written in mm (e.g., 7-7.5mm for women, 8-8.5mm for men).

Once in the correct position, a syringe can be used to inflate the cuff via the pilot line. There is a pilot balloon towards the end of the pilot line, which inflates along with the cuff and allows the anaesthetist to roughly assess how inflated the cuff is (while it is out of sight in the trachea). The pressure in the cuff can be checked with a manometer (pressure sensor) to avoid over or under-inflation. There is a valve on the end of the pilot line that keeps the pilot balloon inflated.

The Murphy’s eye provides an extra hole on the side of the tip that gas can flow through in the event that the main opening at the tip of the ETT becomes occluded (blocked).

A laryngoscope is a metal blade attached to a handle, with a light attached. It is inserted through the mouth and into the pharynx to visualise the vocal cords. An endotracheal tube can be guided along the blade into position in the trachea. A McGrath laryngoscope is a high-tech version of a standard laryngoscope, which has a camera and screen attached so that the vocal cords can be visualised via a live video feed.

A bougie is a device to help with intubation, notably when the vocal cords cannot be visualised. The bougie is inserted into the trachea. The endotracheal tube slides along the bougie into the correct position in the airway. The bougie is then removed, and the endotracheal tube remains in place.

A stylet is another device to help with intubation. It is a stiff metal wire (with a plastic coating) that is inserted into the endotracheal tube before intubation is attempted. It can be bent to hold the endotracheal tube in a specific shape. It is usually used to bend the tip of the endotracheal tube anteriorly towards the trachea (to avoid going posteriorly into the oesophagus).

Awake fibre-optic intubation is a special procedure where the endotracheal tube is inserted with the patient awake, under the guidance of an endoscope (camera). A long thin tube with a camera on the end (endoscope) is inserted through the nose or mouth, down to a position below the vocal cords. The endotracheal tube is then inserted over the top of this tube into the correct position. Then the endoscope is removed, leaving the endotracheal tube in position. This is used where there is restricted mouth opening or difficult anatomy (e.g., after radiotherapy to the neck). Putting the patient to sleep prior to inserting the endotracheal tube is more risky, as a delay in intubation can lead to hypoxia.

Trismus refers to pain and restriction when opening the jaw. This can make intubation more difficult and might need awake fibre-optic intubation.

Supraglottic Airway Devices

A supraglottic airway device (SAD) are an alternative to endotracheal intubation for ventilation. They are very commonly used in both elective and emergency scenarios. They are the first option if intubation fails in a difficult airway scenario.

The tip of the SAD will be located at the top of the oesophagus. The cuff will fit around the opening of the larynx, forming a seal between the device and the airway. The cuff can be inflatable or non-inflatable. SADs with inflatable cuffs are called laryngeal mask airways (LMA). I-gel is a type of non-inflatable SAD that uses a gel-like cuff that moulds to the larynx.

Other Airways

Oropharyngeal (Guedel) airways are inserted into the oropharynx. They are rigid and create an air passage between in front of the teeth and the base of the tongue, maintaining a patent upper airway. They are inserted upside down, then rotated into position once the tip is past the tongue. These are most often used when ventilating the patient via a face mask and bag prior to inserting an SAD or ETT. The size is measured from the centre of the mouth to the angle of the jaw.

Nasopharyngeal airways are slightly flexible tubes inserted through the nose. They create an air passage from outside the nostril to the pharynx (throat). The size is measured from the edge of the nostril to the tragus of the ear. They are often used in emergency scenarios, for example, in A&E or at cardiac arrests. They carry a risk of nosebleeds (epistaxis). A base of skull fracture is a contraindication for inserting a nasopharyngeal airway.

Tracheostomy

A tracheostomy refers to creating a new opening (-ostomy) in the trachea (trache-). A hole is made in the front of the neck with direct access to the trachea. A tracheostomy tube is inserted through the hole into the trachea and held in place with stitches or soft tie around the neck (trach tie). Tracheostomies may be temporary or permanent, depending on the indication.

They can be planned and inserted under a general anaesthetic or performed in an emergency with general or local anaesthetic depending on the circumstances. They are often inserted at the end of head and neck operations, for example, after a laryngectomy procedure (where a permanent tracheostomy will be required).

Indications for a tracheostomy include:

- Respiratory failure where long-term ventilation may be required (e.g., after an acquired brain injury)

- Prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation (e.g., ICU patients that are weak after critical illness)

- Upper airway obstruction (e.g., by a tumour or head and neck surgery)

- Management of respiratory secretions (e.g., in patients with paralysis)

- Reducing the risk of aspiration (e.g., in patients with an unsafe swallow or absent cough reflex)

Tracheostomy tubes are short and curved. There are quite a few variations of tubes, depending on their use. They usually have an outer tube that stays in place, with an inner tube that can be removed to be cleaned or changed. They can have inflatable cuffs to hold them in place and seal the airway, similar to endotracheal tubes.

Difficult Airway

The Difficult Airway Society (DAS) have published guidelines on the steps to take in the case of unanticipated difficulty intubating a patient (DAS guidelines 2015).

There are four stages (summarised):

- Plan A – laryngoscopy with tracheal intubation

- Plan B – supraglottic airway device

- Plan C – face mask ventilation and wake the patient up

- Plan D – cricothyroidotomy

Arterial Line

An arterial line is a special type of cannula inserted into an artery (e.g., the radial artery). The blood pressure can be accurately monitored in real-time using an arterial line. Arterial blood samples (for ABG monitoring) can be taken from the line. Medications are never given through an arterial line.

Central Line

A central line is also called a central venous catheter. This is essentially a long thin tube with several lumens (usually 3-5) that is inserted into a large vein, with the tip located in the vena cava. They may be inserted into the:

- Internal jugular vein

- Subclavian vein

- Femoral vein

They have separate lumens (tubes), which can be used for giving medications or taking blood samples. They last longer and are more reliable than peripheral cannulas. They can also be used for medications that would be too irritating to be given through a peripheral cannula (e.g., inotropes, amiodarone or fluids with a high potassium concentration).

Vas Cath

A Vas Cath is a type of central venous catheter inserted on a temporary basis, usually into the internal jugular or femoral vein. It has two or three lumens. It may be used for short-term haemodialysis (in renal failure).

PICC Line

A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC line) is a type of central venous catheter. A long, thin tube is inserted into a peripheral vein (e.g., in the arm) and fed through the venous system until the tip is in a central vein (the vena cava or right atrium). They contain one or two lumens that are a narrower diameter than a standard central line. They have a low risk of infection, meaning they can stay in for a prolonged period and are useful as medium-term IV access.

Tunnelled Central Venous Catheter

A Hickman line is a type of tunnelled central venous catheter. It is a long, thin catheter that enters the skin on the chest, travels through the subcutaneous tissue (“tunnelled”), then enters into the subclavian or jugular vein, with a tip that sits in the superior vena cava.

There is a cuff (sleeve) that surrounds the catheter near the skin insertion. It promotes adhesion of tissue to the cuff, making the catheter more permanent and providing a barrier to bacterial infection. They can stay in longer-term and be used for regular IV treatment (e.g., chemotherapy or haemodialysis).

Pulmonary Artery Catheter

Pulmonary artery catheters are also known as Swan-Ganz catheters. A pulmonary artery catheter is inserted into the internal jugular vein, through the central venous system, right atrium, right ventricle and into a pulmonary artery. It has a balloon on the end that can be inflated to “wedge” the catheter in a branch of the pulmonary artery. The pressure distal to the wedged balloon can be measured. This gives the pulmonary artery wedge pressure, which gives an indication of the pressures in the left atrium. This is rarely used, mostly used in specialist cardiac centres for close monitoring of cardiac function and response to treatment.

Portacath

A Portacath is a type of central venous catheter. There is a small chamber (port) under the skin at the top of the chest that is used to access the device. This chamber is connected to a catheter that travels through the subcutaneous tissue and into the subclavian vein, with a tip that sits in the superior vena cava or right atrium.

When nothing is attached to the port, the skin remains intact, and there are no lines outside the body. The port can be seen as a bump on the chest wall and felt through the skin (similar to palpitating a pacemaker). When the catheter needs to be accessed, a needle is inserted through the skin into the port, allowing injections to be given or infusions to be set up.

They are fully internalised under the skin, reducing the chance of infection, meaning they last the longest of the options for central venous access. Only specially trained staff are able to access a Portacath. They remain long-term and can be used for regular IV treatment (e.g., chemotherapy).

Last updated August 2021

Now, head over to members.zerotofinals.com and test your knowledge of this content. Testing yourself helps identify what you missed and strengthens your understanding and retention.