Many genetic conditions exhibit a simple inheritance pattern called Mendelian inheritance. This type of inheritance only occurs when the disease is caused by a single abnormal gene on one of the autosomes (not the X or Y sex chromosomes).

Huntington’s disease and cystic fibrosis are examples of diseases with Mendelian inheritance.

The allele coding for Huntington’s disease is dominant. To have the phenotype for Huntington’s disease (to have the disease), only a single copy of the disease allele is required. Huntington’s disease is autosomal dominant.

The allele coding for cystic fibrosis is recessive. To have the phenotype for cystic fibrosis (to have cystic fibrosis), both copies of the gene must be the disease allele. Where there is only one copy of the disease allele, the person is described as a carrier. They carry the disease allele and can pass it on to their offspring, but they do not have the disease. The normal copy of the gene overrides the abnormal copy. Cystic fibrosis is autosomal recessive.

Calculating Autosomal Recessive Inheritance Risk

A common exam scenario tests your ability to calculate the risk of passing a genetic condition to a child. By calculating the four possible outcomes for each scenario, you should always be able to calculate the risk. To illustrate how to do this, there are some practical examples below.

Example One

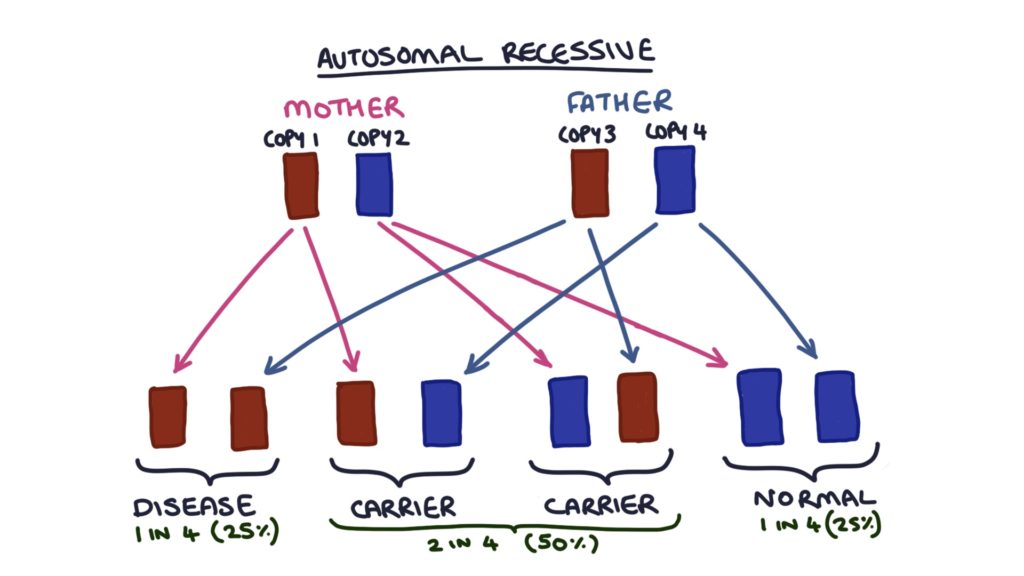

Example one is a scenario in which both parents are carriers of an autosomal recessive condition. Each parent has one disease gene and one normal gene. The parents do not have the disease, but they do have the potential to pass on the disease gene to their children.

Let’s label the copies of the gene that could be inherited from the parents copy 1 to copy 4, with copy 1 and 2 coming from the father and copy 3 and 4 coming from the mother. The child inherits one copy from the father and one from the mother. Let’s say copy 1 and 3 are autosomal recessive disease genes, and copy 2 and 4 are normal.

The four possible outcomes for inheritance of this gene are:

- Outcome 1: Copy 1 and copy 3 (two abnormal copies, therefore the child has the disease)

- Outcome 2: Copy 1 and copy 4 (one abnormal copy and one normal copy, therefore the child is a carrier)

- Outcome 3: Copy 2 and copy 3 (one abnormal copy and one normal copy, therefore the child is a carrier)

- Outcome 4: Copy 2 and copy 4 (two normal copies)

Each child of these parents has a 1 in 4 (or 25%) probability of having the disease, a 2 in 4 (or 50%) probability of being a carrier and a 1 in 4 (or 25%) probability of being unaffected.

Example Two

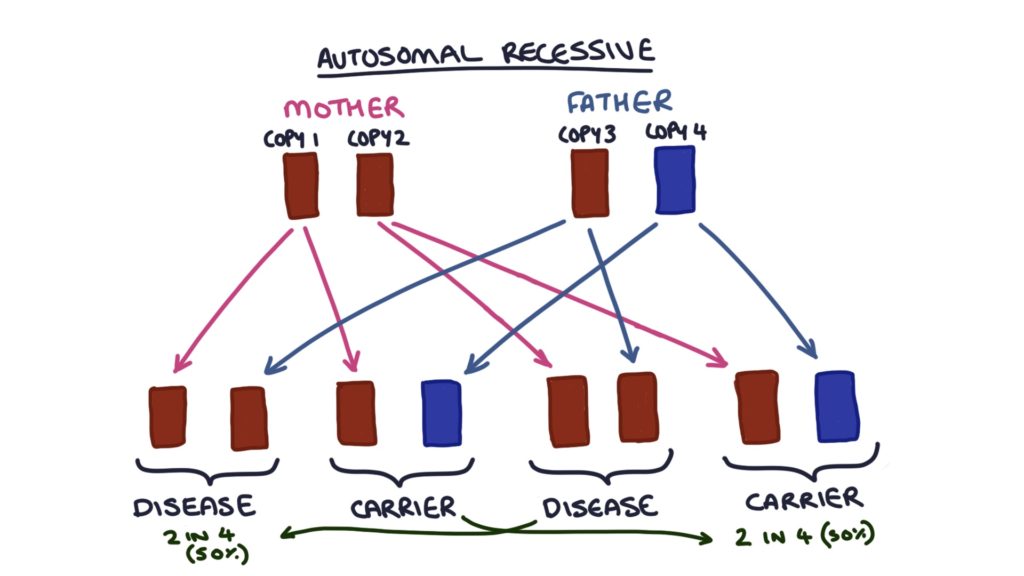

Example two is a scenario in which one parent has an autosomal recessive disease and the other parent is a carrier. Copy 1 and 2 of the gene (from the affected parent) are abnormal, whilst in the other parent (the carrier) copy 3 is abnormal and copy 4 is normal. There are four possible outcomes to the inheritance of this gene:

- Outcome 1: copy 1 and copy 3 (the child has the disease)

- Outcome 2: copy 1 and copy 4 (the child is a carrier)

- Outcome 3: copy 2 and copy 3 (the child has the disease)

- Outcome 4: copy 2 and copy 4 (the child is a carrier)

Each child of these parents has a 50% probability of having the disease and a 50% probability of being a carrier.

Example Three

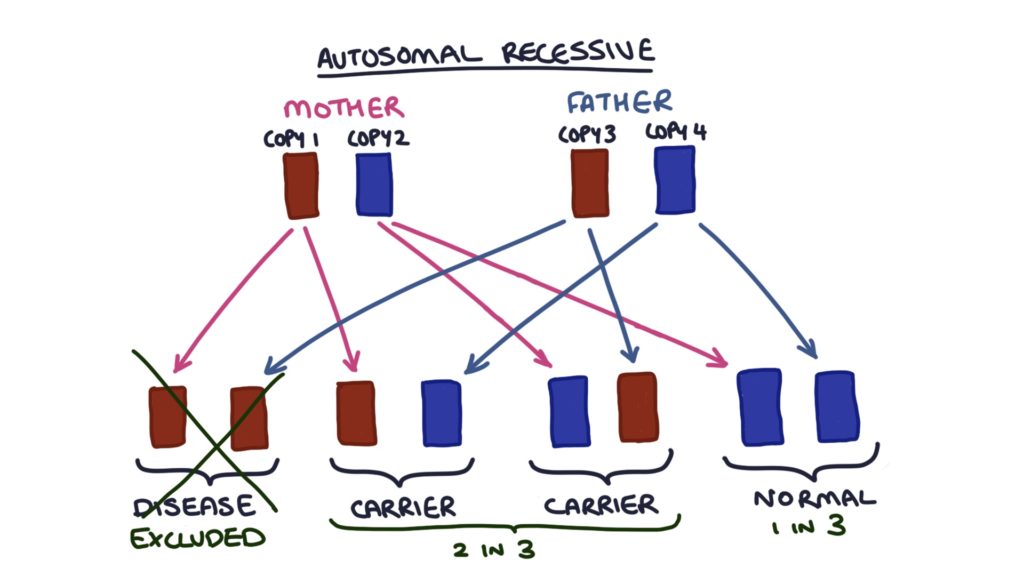

Example three is a scenario in which both parents are healthy (they do not have the phenotype), but we are not told their genetic status. One child has an autosomal recessive disease, such as cystic fibrosis. The task is to calculate the probability of their healthy sibling being a carrier.

Two abnormal copies are required for the first child to have the disease. Therefore, both parents must be carriers. If one parent had two abnormal copies, they would also have the disease.

Therefore, the possible outcomes for future children are the same as in example one:

- Outcome 1 has two abnormal copies (they have the disease)

- Outcome 2 has one abnormal copy and one normal copy (they are a carrier)

- Outcome 3 has one abnormal copy and one normal copy (they are a carrier)

- Outcome 4 has two normal copies (they neither have the disease nor are a carrier)

The risk of each child being a carrier is 2 in 4, or 50%. However, 2 in 4 is not the answer to the question, because the sibling in the question is healthy. We can exclude outcome 1, as we know they do not have the disease. The possible genetic outcomes for the second child are outcomes 2, 3, or 4. In two of these outcomes (2 and 3), the child is a carrier. Therefore, the risk of the second child being a carrier is 2 in 3 (67%).

TOM TIP: This third scenario is a typical exam question. Students are tricked into putting 2 in 4 (50%) because they forget to exclude the outcome in which the child has the disease. Keep a close eye out for this. If in doubt, write out all the possible outcomes and don’t rush.

Calculating Autosomal Dominant Inheritance Risk

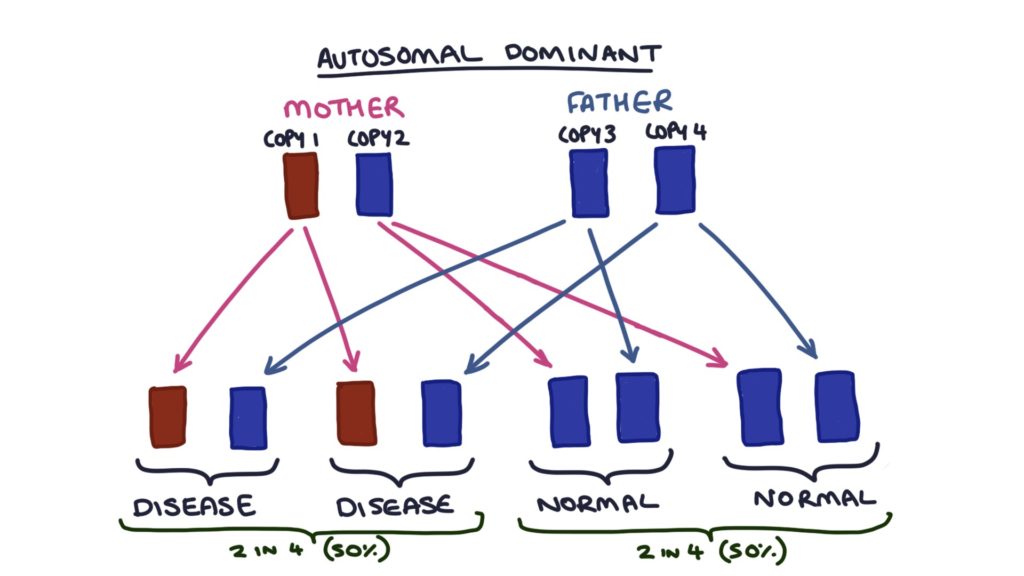

The same method can be used to calculate the risk of inheriting an autosomal dominant condition. For example, let’s calculate the possible outcomes when one parent has an autosomal dominant condition, and the other parent is disease-free.

We need to know whether the affected parent has one or two copies of the disease allele, because either way, they will have the condition. We can find this out through genetic testing or by asking about that person’s parents. If the affected person has only one affected parent, we know they only have one copy of the disease gene. If they had two affected parents, they may have two copies of the disease gene.

In the vast majority of cases, a person with an autosomal dominant condition has a single abnormal copy of the gene. Let’s assume they only have one abnormal copy of the disease gene.

Let’s assume copy 1 is the allele that codes for the disease. The possible outcomes are as follows:

- Outcome 1: copy 1 and copy 3 (one abnormal copy and one normal copy, therefore they have the disease)

- Outcome 2: copy 1 and copy 4 (one abnormal copy and one normal copy, therefore they have the disease)

- Outcome 3: copy 2 and copy 3 (two normal copies)

- Outcome 4: copy 2 and copy 4 (two normal copies)

Therefore, the children of these parents have a 2 in 4 (or 50%) chance of having the disease, and a 2 in 4 (or 50%) chance of being unaffected.

Last updated November 2025

Now, head over to members.zerotofinals.com and test your knowledge of this content. Testing yourself helps identify what you missed and strengthens your understanding and retention.