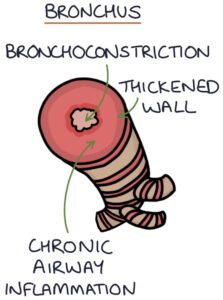

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway disease leading to variable airway obstruction. The smooth muscle in the airways is hypersensitive and responds to stimuli by constricting and causing airflow obstruction. This bronchoconstriction is reversible with bronchodilators, such as inhaled salbutamol.

Asthma is one of several atopic conditions, including eczema, hay fever and food allergies. Patients with one of these conditions are more likely to have others. These conditions characteristically run in families.

Asthma typically presents in childhood. However, it can present at any age. Adult-onset asthma refers to asthma presenting in adulthood. Occupational asthma refers to asthma caused by environmental triggers in the workplace.

The severity of symptoms of asthma varies enormously between individuals. Acute asthma exacerbations involve rapidly worsening symptoms and can quickly become life-threatening.

Presentation

Symptoms are episodic, meaning there are periods where the symptoms are worse and better. There is diurnal variability, meaning the symptoms fluctuate at different times of the day, typically worse at night.

Typical symptoms are:

- Shortness of breath

- Chest tightness

- Dry cough

- Wheeze

Symptoms should improve with bronchodilators. No response to bronchodilators reduces the likelihood of asthma.

Patients may have a history of other atopic conditions, such as eczema, hayfever and food allergies. They often have a family history of asthma or atopy.

Examination is generally normal when the patient is well. A key finding with asthma is a widespread “polyphonic” expiratory wheeze.

TOM TIP: A localised monophonic wheeze is not asthma. The top differentials of a localised wheeze are an inhaled foreign body, tumour or a thick sticky mucus plug obstructing an airway. A chest x-ray is the next step.

Typical Triggers

Certain environmental triggers can exacerbate the symptoms of asthma. These vary between individuals:

- Infection

- Nighttime or early morning

- Exercise

- Animals

- Cold, damp or dusty air

- Strong emotions

TOM TIP: Beta-blockers, particularly non-selective beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen or naproxen), can worsen asthma. These are worth remembering.

Investigations

Spirometry is the test used to establish objective measures of lung function. It involves different breathing exercises into a machine that measures volumes of air and flow rates and produces a report. A FEV1:FVC ratio of less than 70% suggests obstructive pathology (e.g., asthma or COPD).

Reversibility testing involves giving a bronchodilator (e.g., salbutamol) before repeating the spirometry to see if this impacts the results. NICE says a greater than 12% increase in FEV1 on reversibility testing supports a diagnosis of asthma.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) measures the concentration of nitric oxide exhaled by the patient. Nitric oxide is a marker of airway inflammation. The test involves a steady exhale for around 10 seconds into a device that measures FeNO. NICE say a level above 40 ppb is a positive test result, supporting a diagnosis. Smoking can lower the FeNO, making the results unreliable.

Peak flow variability is measured by keeping a peak flow diary with readings at least twice daily over 2 to 4 weeks. NICE says a peak flow variability of more than 20% is a positive test result, supporting a diagnosis.

Direct bronchial challenge testing is the opposite of reversibility testing. Inhaled histamine or methacholine is used to stimulate bronchoconstriction, reducing the FEV1 in patients with asthma. NICE say a PC20 (provocation concentration of methacholine causing a 20% reduction in FEV1) of 8 mg/ml or less is a positive test result.

Diagnosis

The NICE guidelines (2020) recommend initial investigations in patients with suspected asthma:

- Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

- Spirometry with bronchodilator reversibility

Where there is diagnostic uncertainty after initial investigations, the next step is testing the peak flow variability.

Where there is still uncertainty, the next step is a direct bronchial challenge test with histamine or methacholine.

The BTS/SIGN guidelines (revised 2019) are similar to the NICE guidelines. They recommend categorising patients into a high, intermediate or low probability of asthma based on clinical features and investigation results, then assessing the response to treatment before making a diagnosis if there is a good response.

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines (2022) are relatively similar on diagnosis, other than suggesting that FeNO testing is not useful in making or excluding a diagnosis of asthma.

Pharmacology

Beta-2 adrenergic receptor agonists are bronchodilators (they open the airways). Adrenalin acts on the smooth muscle of the airways to cause relaxation. Stimulating the adrenalin receptors dilates the bronchioles and reverses the bronchoconstriction present in asthma. Short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABA), such as salbutamol, work quickly, but the effects last only a few hours. They are used as reliever or rescue medication during acute worsening of asthma symptoms. Long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABA), such as salmeterol, are slower to act but last longer.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), such as beclometasone, reduce the inflammation and reactivity of the airways. These are used as maintenance or preventer medications to control symptoms long-term and are taken regularly, even when well.

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA), such as tiotropium, work by blocking acetylcholine receptors. Acetylcholine receptors are stimulated by the parasympathetic nervous system and cause contraction of the bronchial smooth muscles. Blocking these receptors dilates the bronchioles and reverses the bronchoconstriction present in asthma.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists, such as montelukast, work by blocking the effects of leukotrienes. Leukotrienes are produced by the immune system and cause inflammation, bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion in the airways.

Theophylline works by relaxing the bronchial smooth muscle and reducing inflammation. Unfortunately, it has a narrow therapeutic window and can be toxic in excess, so monitoring plasma theophylline levels is required.

Maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) involves a combination inhaler containing an inhaled corticosteroid and a fast and long-acting beta-agonist (e.g., formoterol). This replaces all other inhalers, and the patient uses this single inhaler both regularly as a preventer and also as a reliever when they have symptoms.

Long-Term Management

The principles of using the stepwise ladder are to:

- Start at the most appropriate step for the severity of the symptoms

- Review at regular intervals based on severity (e.g., 4-8 weeks after adjusting treatment)

- Add additional treatments as required to control symptoms completely

- Aim to achieve no symptoms or exacerbations on the lowest dose and number of treatments

- Always check inhaler technique and adherence when reviewing medications

The BTS/SIGN guidelines on asthma (2019) suggest the following steps (adding drugs at each stage):

- Short-acting beta-2 agonist inhaler (e.g. salbutamol) as required

- Inhaled corticosteroid (low dose) taken regularly

- Long-acting beta-2 agonists (e.g., salmeterol) or maintenance and reliever therapy (MART)

- Increase the inhaled corticosteroid or add a leukotriene receptor antagonist (e.g., montelukast)

- Specialist management (e.g., oral corticosteroids)

The NICE guidelines on asthma (2017) suggest the following steps (adding drugs at each stage):

- Short-acting beta-2 agonist inhaler (e.g. salbutamol) as required

- Inhaled corticosteroid (low dose) taken regularly

- Leukotriene receptor antagonist (e.g., montelukast) taken regularly

- Long-acting beta-2 agonists (e.g., salmeterol) taken regularly

- Consider changing to a maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) regime

- Increase the inhaled corticosteroid to a moderate dose

- Consider high-dose inhaled corticosteroid or additional drugs (e.g., LAMA or theophylline)

- Specialist management (e.g., oral corticosteroids)

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines (2022) recommend that all patients should be on an inhaled corticosteroid and should not be managed with a SABA (e.g., salbutamol) alone. The first step of their ladder is a combination inhaler containing a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid plus formoterol as required. The second step is maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) with the same inhaler. The NICE and BTS/SIGN guidelines predate the GINA guidelines and may change.

Additional management includes:

- Individual written asthma self-management plan

- Yearly flu jab

- Yearly asthma review when stable

- Regular exercise

- Avoid smoking (including passive smoke)

- Avoiding triggers where appropriate

Acute Exacerbation

An acute exacerbation of asthma involves a rapid deterioration in symptoms. Any typical asthma triggers, such as infection, exercise or cold weather, could set off an acute exacerbation.

Presenting features of an acute exacerbation are:

- Progressively shortness of breath

- Use of accessory muscles

- Raised respiratory rate (tachypnoea)

- Symmetrical expiratory wheeze on auscultation

- The chest can sound “tight” on auscultation, with reduced air entry throughout

On arterial blood gas analysis, patients initially have respiratory alkalosis, as a raised respiratory rate (tachypnoea) causes a drop in CO2. A normal pCO2 or low pO2 (hypoxia) is a concerning sign, as it means they are getting tired, indicating life-threatening asthma. Respiratory acidosis due to high pCO2 is a very bad sign.

Grading Acute Asthma

Moderate exacerbation features:

- Peak flow 50 – 75% best or predicted

Severe exacerbation features:

- Peak flow 33-50% best or predicted

- Respiratory rate above 25

- Heart rate above 110

- Unable to complete sentences

Life-threatening exacerbation features:

- Peak flow less than 33%

- Oxygen saturations less than 92%

- PaO2 less than 8 kPa

- Becoming tired

- Confusion or agitation

- No wheeze or silent chest

- Haemodynamic instability (shock)

The wheeze disappears when the airways are so tight that there is no air entry. This is ominously described as a silent chest and is a sign of life-threatening asthma.

Management of Acute Asthma

Patients with an acute exacerbation of asthma can deteriorate quickly. Acute asthma is potentially life-threatening. Treatment should be aggressive and they should be escalated early to seniors and intensive care. Treatment decisions, particularly intravenous aminophylline, salbutamol and magnesium, should involve experienced seniors.

Mild exacerbations may be treated with:

- Inhaled beta-2 agonists (e.g., salbutamol) via a spacer

- Quadrupled dose of their inhaled corticosteroid (for up to 2 weeks)

- Oral steroids (prednisolone) if the higher ICS is inadequate

- Antibiotics only if there is convincing evidence of bacterial infection

- Follow-up within 48 hours

Moderate exacerbations may additionally be treated with:

- Consider hospital admission

- Nebulised beta-2 agonists (e.g., salbutamol)

- Steroids (e.g., oral prednisolone or IV hydrocortisone)

Severe exacerbations may additionally be treated with:

- Hospital admission

- Oxygen to maintain sats 94-98%

- Nebulised ipratropium bromide

- IV magnesium sulphate

- IV salbutamol

- IV aminophylline

Life-threatening exacerbations may additionally be treated with:

- Admission to HDU or ICU

- Intubation and ventilation

The decision to intubate a patient with life-threatening asthma is generally made early as it is very difficult to intubate with severe bronchoconstriction.

Serum potassium needs monitoring with salbutamol treatment, which causes potassium to be absorbed from the blood into the cells, resulting in hypokalaemia (low potassium). Salbutamol also causes tachycardia (fast heart rate) and can cause lactic acidosis.

After an acute attack, management involves:

- Optimising long-term asthma management

- Individual written asthma self-management plan

- Considering a rescue pack of oral steroids to start early in an exacerbation

- NICE suggest referral to a specialist after 2 attacks in 12 month

Last updated June 2023