Leukaemia is cancer of a particular line of stem cells in the bone marrow, causing unregulated production of a specific type of blood cell.

Types

The types of leukaemia can be classified depending on how rapidly they progress (chronic is slow and acute is fast) and the cell line that is affected (myeloid or lymphoid) to make four main types:

- Acute myeloid leukaemia (rapidly progressing cancer of the myeloid cell line)

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (rapidly progressing cancer of the lymphoid cell line)

- Chronic myeloid leukaemia (slowly progressing cancer of the myeloid cell line)

- Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (slowly progressing cancer of the lymphoid cell line)

Other rarer types, such as acute promyelocytic leukaemia, are less like to appear in exams.

Most types of leukaemia occur in patients over 60-70. The exception is acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, which most commonly affects children under five years.

TOM TIP: The key differentiating features to remember for exams are:

- ALL is the most common leukaemia in children and is associated with Down syndrome

- CLL is associated with warm haemolytic anaemia, Richter’s transformation and smudge cells

- CML has three phases, including a long chronic phase, and is associated with the Philadelphia chromosome

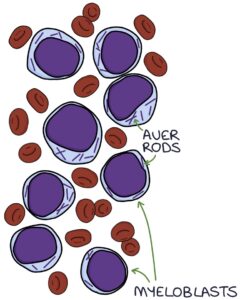

- AML may result in a transformation from a myeloproliferative disorder and is associated with Auer rods

Pathophysiology

A genetic mutation in one of the precursor cells in the bone marrow leads to excessive production of a single type of abnormal white blood cell.

The excessive production of a single type of cell can suppress the other cell lines, causing the underproduction of different cell types. This can result in pancytopenia, which is a combination of low red blood cells (anaemia), white blood cells (leukopenia) and platelets (thrombocytopenia).

Presentation

The presentation of leukaemia is relatively non-specific. An urgent full blood count is required when leukaemia is a differential for a presentation. Potential presenting features include:

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Pallor due to anaemia

- Petechiae or bruising due to thrombocytopenia

- Abnormal bleeding

- Lymphadenopathy

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Failure to thrive (children)

Differential Diagnosis of Petechiae

One key presenting feature of leukaemia is bleeding under the skin due to thrombocytopenia. Bleeding under the skin causes non-blanching lesions. These lesions are called different things based on the size of the lesions:

- Petechiae are less than 3 and caused by burst capillaries

- Purpura are 3 – 10mm

- Ecchymosis is larger than 1cm

The top differentials for a non-blanching rash caused by bleeding under the skin are:

- Leukaemia

- Meningococcal septicaemia

- Vasculitis

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP)

- Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- Traumatic or mechanical (e.g., severe vomiting)

- Non-accidental injury

Consider non-accidental injury (abuse) as a differential, particularly in children and vulnerable adults.

Diagnosis

The NICE guidelines on suspected cancer (2021) recommend a full blood count within 48 hours for patients with suspected leukaemia. They recommend children or young people with petechiae or hepatosplenomegaly are sent for immediate specialist assessment.

A full blood count is the initial investigation.

A blood film is used to look for abnormal cells and inclusions.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a very non-specific marker of tissue damage. It is often raised in leukaemia but also in other cancers and many non-cancerous conditions, including after heavy exercise. It is not helpful as a screening test but may be used for specialist assessment and monitoring.

Bone marrow biopsy is used to analyse the cells in the bone marrow to establish a definitive diagnosis of leukaemia.

CT and PET scans may be used to help stage the condition.

Lymph node biopsy can be used to assess abnormal lymph nodes.

Genetic tests (looking at chromosomes and DNA changes) and immunophenotyping (looking for specific proteins on the surface of the cells) may be performed to help guide treatment and prognosis.

Bone Marrow Biopsy

Bone marrow biopsy is usually taken from the iliac crest. It involves a local anaesthetic and a specialist needle. The options are aspiration or trephine. Bone marrow aspiration involves taking a liquid sample of cells from within the bone marrow. Bone marrow trephine involves taking a solid core sample of the bone marrow and provides a better assessment of the cells and structure.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) affects one of the lymphocyte precursor cells, causing acute proliferation of a single type of lymphocyte, usually B-lymphocytes. Excessive accumulation of these cells replaces the other cell types in the bone marrow, leading to pancytopenia.

ALL most often affects children under five but can also affect older adults. It is more common with Down’s syndrome. It can be associated with the Philadelphia chromosome (but this is more associated with chronic myeloid leukaemia).

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is where there is slow proliferation of a single type of well-differentiated lymphocyte, usually B-lymphocytes. It usually affects adults over 60 years of age. It is often asymptomatic but can present with infections, anaemia, bleeding and weight loss. It may cause warm autoimmune haemolytic anaemia.

Richter’s transformation refers to the rare transformation of CLL into high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

Smear or smudge cells are ruptured white blood cells that occur while preparing the blood film when the cells are aged or fragile. They are particularly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia

Chronic myeloid leukaemia has three phases:

- Chronic phase

- Accelerated phase

- Blast phase

The chronic phase is often asymptomatic, and patients are diagnosed after an incidental finding of a raised white cell count. This phase can last several years before progressing.

The accelerated phase occurs when the abnormal blast cells take up a high proportion (10-20%) of the bone marrow and blood cells. In the accelerated phase, patients are more symptomatic and develop anaemia, thrombocytopenia and immunodeficiency.

The blast phase follows the accelerated phase and involves an even higher proportion (over 20%) of blast cells in the blood. The blast phase has severe symptoms and pancytopenia and is often fatal.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia is particularly associated with the Philadelphia chromosome. This refers to an abnormal chromosome 22 caused by a reciprocal translocation (swap) of genetic material between a section of chromosome 9 and chromosome 22. This translocation creates an abnormal gene sequence called BCR-ABL1, which codes for an abnormal tyrosine kinase enzyme that drives the proliferation of the abnormal cells.

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia

There are many subtypes of acute myeloid leukaemia, with slightly different cytogenetics and presentations.

It can present at any age but normally presents from middle age onwards. It can be the result of a transformation from a myeloproliferative disorder, such as polycythaemia ruby vera or myelofibrosis.

A blood film and bone marrow biopsy will show a high proportion of blast cells. Auer rods in the cytoplasm of blast cells are a characteristic finding in AML.

General Management

An oncology and haematology multi-disciplinary team will coordinate treatment. Leukaemia is mainly treated with chemotherapy and targeted therapies, depending on the type and individual features.

Examples of targeted therapies include (mainly used in CLL):

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib)

- Monoclonal antibodies (e.g., rituximab, which targets B-cells)

Other treatments options include:

- Radiotherapy

- Bone marrow transplant

- Surgery

Complications of Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy comes with a long list of complications and adverse effects:

- Failure to treat cancer

- Stunted growth and development in children

- Infections due to immunosuppression

- Neurotoxicity

- Infertility

- Secondary malignancy

- Cardiotoxicity (heart damage)

- Tumour lysis syndrome

Tumour Lysis Syndrome

Tumour lysis syndrome results from chemicals released when cells are destroyed by chemotherapy, resulting in:

- High uric acid

- High potassium (hyperkalaemia)

- High phosphate

- Low calcium (as a result of high phosphate)

Uric acid can form crystals in the interstitial space and tubules of the kidneys, causing acute kidney injury. Hyperkalaemia can cause cardiac arrhythmias. The release of cytokines can cause systemic inflammation.

Very good hydration and urine output before chemotherapy is required in patients at risk of tumour lysis syndrome. Allopurinol or rasburicase may be used to suppress the uric acid levels.

Last updated August 2023