For my science and maths A-level exams, I discovered that everything I needed to know for the exam could be found within one book, and the same content came up year after year on the exams. I studied the book and practised all the past papers multiple times before the exam. There were no surprises on the exam day, and I scored 100% on many of the exams.

Later, I studied medicine at Manchester Medical School, where we did problem-based learning. We had small group sessions, discussing a case and identifying topics we needed to learn. At the end of the semester, the exam tested us on the content we were supposed to have identified as necessary during these small group sessions. Trying to work out what we needed to know could be frustrating.

I tried learning from textbooks but often found the books did not cover everything on the exams. Even then, I felt like I was stabbing in the dark, trying to figure out what was important and what was not. I often missed important content and wasted hours going down rabbit holes learning content with little value. In the early years, I struggled to answer many of the exam questions and came away with mediocre results.

A common frustration I hear from medical students is that their medical school does not tell them when to learn or what will come up in exams. I have three main explanations for why this is the case:

- Medicine is open-ended and constantly changing subject. It would be almost impossible for the medical school team to define what needs to be learned and keep that up to date.

- They want you to become a self-directed learner. They want you to learn how to learn the relevant and important information for yourself. You need to continue learning after graduation and throughout your career.

- Giving you all the content that will come up on the exams will make them too easy. To get to medical school, you need to be good at exams. If everyone were told exactly what would come up, everyone would score very high there would be nothing to differentiate between the best students and those struggling.

Accepting that medical schools have their reasons for being vague about what is coming up on the exams, what can you do about it?

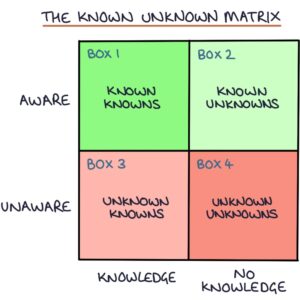

The Known-Unknown Matrix

This matrix can help us understand the solutions to some of the biggest challenges in learning medicine.

Box 1: Known knowns are the things that you are aware of knowing. Ideally, the day before your exam, this box is full of all the content you need to fly through without too much difficulty.

Box 2: Known unknowns are the things you know you need to learn. Ideally, you have an organised collection of notes containing all the content you need for your exam, with plenty of time to go through it for several repetitions before the exam.

Box 3: Unknown knowns are the things you know but do not realise you already know. For example, you don’t realise that if a question on the anatomy of the heart came up, you would have a good shot at getting it right. This is a problem because you may waste time studying the anatomy of the heart when you should focus on your weaknesses by reading up on another topic instead.

Box 4: Unknown unknowns are the most dangerous of all. These are the things that come up on the exam, or when seeing patients, you had no idea you needed to know and completely missed in your revision. They may also be what you think falls into box 1, believing you know, when you are unaware that you do not know it.

I did so well in my science and maths A-level exams because all the content that could come up on the exam fell into box 1 and box 2. Either I already knew the content, or I knew exactly what I needed to learn before the exam. In contact, learning medicine is plagued by content in box 4, the dreaded unknown unknowns.

The ultimate aim of learning medicine is to move as much content from boxes 2, 3 and 4 into box 1, ready for your exams and working as a doctor. Let's tackle one box at a time.

Let's start with the unknown knowns

The main danger to leaving content in box 3 (unknown knowns) is that you waste time revising content that you already know while neglecting content that you don't know.

It is very important to know when you are sufficiently good at a topic so that you can move on to something else. This involves moving content from box 3 (unknown knowns) to box 1 (known knowns). How do you do this?

The simple answer is that you test yourself and track your learning. I will be covering testing and tracking in great detail elsewhere.

Secondly, let's address the known unknowns box

Most of this book is designed to help you transfer information from box 2 (known unknowns) to box 1 (known knowns). Taking information and transferring it to your long-term memory is relatively straightforward when you know exactly what you need to learn. I recommend a combination of spaced repetition, active reading, testing and tracking. We will cover all of these in far more detail later.

Finally, let's address the unknown unknowns

I will argue that the way to tackle content in box 4 (unknown unknowns) is first to transfer them to box 2 (known unknowns). The way to do this is to compile a set of notes, which you will later use to move content from box 2 (known unknowns) to box 1 (known knowns).

However, my recommendation for compiling a set of notes might look very different from what you might think. I am not talking about handwritten or re-typed notes. I am talking about a much faster process of collecting and compiling notes.

When taking notes, many people think they are transferring that information from box 4 (unknown unknowns) straight to box 1 (known knowns). This is not the case. They sit down and copy notes from textbooks or lecture slides into their digital or physical notepad. They might say, "this is how I learn best", believing that this process consolidates the information in their memory. During this process, there will be a minimal amount of content stored in their long-term memory, but the vast majority will go in, get processed in the working memory, and then get dismissed as they write it down on the page. There is no active recall, no strain to remember that information and no application of the knowledge. The brain is smart enough to know that the long-term retention of that information has been delegated to the notepad, so there is no need to remember it. To be clear, making notes on a topic is not a good way of transferring information from box 4 (unknown unknowns) to box 1 (known knowns).

I recommend collecting and organising content as rapidly as possible when compiling notes. Do not try to learn them at this stage. You are gathering your set of known unknowns in preparation for learning it, filling box 2 (known unknowns) with all the content you need to know. Once you have collected your set notes (your known unknowns), you can apply the principles on this site to learn them most efficiently.

I would suggest starting with a pre-existing set of notes. You could start with one of the Zero to Finals books. The Zero to Finals books were designed for this exact purpose. Congratulations, you have immediately transferred 80-90% of what you need to know from box 4 (unknown unknowns) to box 2 (known unknowns) and saved yourself hundreds of hours of note-making.

Once you have a baseline set of notes, you can immediately apply the principles of space repetition, active reading, testing and tracking to that content, transferring it from box 2 (known unknowns) to box 1 (known knowns). You will quickly become familiar with the content, becoming aware of what fits into box 1 (known knowns) and box 2 (known unknowns). It will be easy for you to identify something that fits into box 4 (unknown unknowns) when you come across it.

When you are on clinical placements, seeing patients, doing practice questions, attending lectures, studying with peers or reading around the topic, you will start picking up on bits of information you realise you are not familiar with and are not in your set of notes. When this happens, jot it down in a notepad, on a piece of paper or on your phone to remind yourself of this unknown unknown.

Later, when you have some time, go back through your list of unknown unknowns. Go online or look it up in a textbook and, as quickly as possible, summarise the key points you need to remember about that condition. Add this summary to your set of notes.

This process allows you to identify unknown unknowns and convert them to known unknowns.

A final thing to note is that it is possible to get carried away trying to put together the most comprehensive set of notes possible out of fear that you might miss something. You have a long career ahead and will be learning until the day you retire. You can't know everything in medicine for your next set of exams. If you collect together too many notes, you will not have the time to transfer everything from box 2 (known unknowns) to box 1 (known knowns).

Be realistic when putting together your notes and make it achievable to do multiple repetitions of learning that content. The set of notes I threw together for my finals was barely a skeleton of what I know now. My list of unknown unknowns was enormous. Yet I was able to graduate with honours. Don't let perfection stop you from getting good grades.