In order to get into medical school, you will have done pretty well in school. That means a fair number of exams, along with the studying and revision required to sit them. However, there is a huge difference between revision for GCSEs and A-levels and learning medicine.

When I sat my A-levels, I developed a very solid revision strategy. I knew that the official textbooks contained everything I needed to know for the exam, and I had access to past papers dating back 5 or so years, along with the mark schemes. I repeatedly read through the textbooks and practised the past papers. Then, on the exam day, I knew everything that could come up and exactly what the mark sheet wanted me to write. I ended up scoring 100% on many of my A-level exams.

When I arrived at medical school I was in for a rude awakening. There was no textbook that contained everything I needed to know. There were no past papers. There was no mark scheme to memorise. There seemed to be no limits to what I had to learn and what the exams could test me on. Despite my best efforts, there were exam questions that asked about things I didn’t even know I needed to know. I was held back by all the things I didn’t know that I didn’t know. My A-level strategy was not going to work here. I needed new strategies.

We are going to go into lots of detail about how to create a new study strategy for learning medicine. I will share the evidence-based principles that I recommend you build on when creating your strategy. I will also share the strategy that has most consistently worked for me. But first, there is a very important question to address:

How do you know whether your new study strategy works?

Every new medication for a medical condition needs to be evidence-based. This involves a process of careful, controlled research. Over the course of different trial phases, large numbers of people are given the medication and carefully followed up to determine variables such as the safety, side effects, efficacy and optimal dosage.

We use a similar approach when prescribing a new medication to an individual patient. Most long-term medications for chronic conditions need a certain amount of monitoring. If a patient is diagnosed with hypertension and you start amlodipine at 5mg per day, you would not send that patient away and tell them to have faith that it will work perfectly forever. You would follow them up after a short period to see whether their blood pressure is adequately controlled and whether they have any side effects. You may need to increase the dose, change to an alternative or add a second medication. They would then be periodically reviewed to see whether it remains the optimal treatment.

The same, evidence-based approach should be taken to developing a new study strategy. There is a wealth of psychological research that can be used as the basis for building your strategy for learning medicine. Psychologists have been testing the effects of different study techniques for decades. Some of the techniques have very robust findings. We will explore these in detail over the coming sections.

Just like starting a new medication for a patient, once you design and create your study strategy based on evidence-based principles, you still need to assess how it works for you as an individual. That involves regular reviews to determine whether it is effective and whether it needs changing, tweaking or adding to.

Feedback Loops

Having a feedback loop is essential to learning and getting better at anything. In the absence of an effective feedback loop, you run the risk of wasting time, or even worse, forming bad habits.

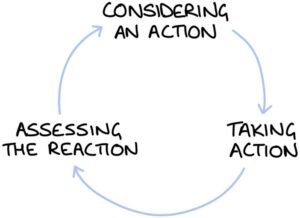

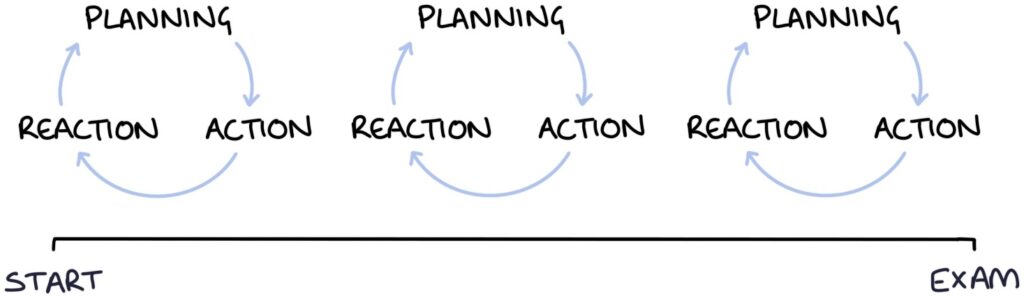

A simple feedback loop looks like this:

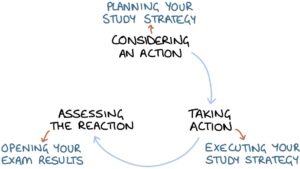

You start by considering an action. This is the planning phase of your study strategy. This is the stage where you might decide you are going to create a set of flashcards and use them to prepare for your upcoming exam.

The next step is taking action. This is where you start making the flashcards. You sit in the library, pouring through books and jotting down the relevant facts on your set of flashcards. Then, as the exam approaches, you flick through the flashcards, trying to learn the content written on them.

The next step is assessing the reaction. For many people, this happens when they sit their summative exam. They come out of the exam hall feeling unsure about how the exam went. They wait for the results and then nervously open them when the time comes. It is only at this point that they know whether the study strategy worked.

If you wait until results day to assess the reaction, you are relying on a single feedback loop to determine the effects of your study strategy.

There are a number of issues with waiting until results day to assess the reaction to your study strategy.

Firstly, it is too late to change anything - the result is summative. If you are lucky, your revision strategy worked and you passed. If you didn’t, you failed and will have to resit the exam. In the worst-case scenario, you have to drop out of the course.

Secondly, the feedback is usually pretty unhelpful. Knowing that you scored a certain percentage does not tell you very much about what worked and what didn’t work in your study strategy. Sure, if you scored 98% you know you are on the right track, and if you score 20% on a multiple-choice question exam, you know you are doing something horribly wrong. But most results are pretty vague.

Thirdly, there are many confounding variables that make it difficult to say whether your strategy worked or not. The exam may have been poorly designed, you might not have slept well the night before, you may have had a cold, you may have overlooked a single vital topic in your revision or you may have guessed particularly well or badly that day.

Finally, summative exams are not always the best measure of whether you are actually progressing well towards being a knowledgable, competent doctor.

Sometimes it may seem that your progress through medical school is determined by a series of multiple-choice exams and OSCEs. However, medical schools also use many other measures to determine your progress. There are many workplace-based assessments, case-based discussions, supervisors' reports and portfolio assessments that are designed to flag up students that are having issues. Theoretically, you could fly through exams but perform poorly in the real world, when actually interacting and managing patients. Equally, we all know people that are fantastic in a clinical setting but struggle to pass exams.

Increase The Number Of Feedback Loops

When you wait until results day to assess the reaction, you are relying on a single feedback loop to determine the effects of your study strategy.

To create the optimal revision strategy, you need to increase the number of feedback loops. Each time you complete a feedback loop, you can adapt your study strategy to make it more effective. The more feedback loops you have, the more opportunities you have to improve the strategy.

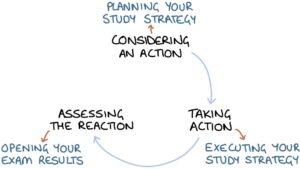

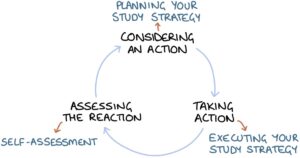

Each individual feedback loop will look like this:

Over time, you will keep repeating that loop from the start of your studies until you reach your exam:

Think of your revision strategy as single-subject research. You want to design a strategy, and then regularly take measurements to assess whether that strategy is working. The more data or feedback you collect on how well the strategy is working, the more information you have available to improve your strategy.

Assessing The Reaction

The next question is how you should assess whether your strategy is working. Your first thought may be that this involves doing lots of practice questions to see what your scores are. However, there is so much more that you can measure to help optimise your revision strategy.

I often ask people what they find most difficult about learning medicine and preparing for exams. One of the most common replies I get is a variation of “I struggle to stay motivated” or “I find it difficult to focus on learning the content”.

One of the variables that will determine your motivation or ability to focus on learning the content is your revision strategy. So why shouldn’t you measure motivation or focus as a reaction to your study strategy, and alter your strategy to improve your motivation?

For example:

Let's say your strategy involves using flashcards. You write everything you need to know for a condition on a flashcard. Then, you go through the flashcards, trying to memorise the content on each card. At the end of each day, you write a few lines in a journal to say how you felt revising that day, rating your motivation and focus on a scale of 0 - 10. You also record the number of focused hours you spent learning and how many flashcards you covered.

You find that you are consistently struggling to focus, are bored and can only do a few flashcards before you get distracted. Sometimes you struggle to do any revision at all. Because you are consciously monitoring this, you have identified that you need to adapt your strategy to make it more engaging and motivating.

You alter the flashcards so that on one side there are questions and on the other side there are answers. You create a scoring system, so you are able to measure what percentage of answers you get correct for each flashcard. This turns revision into a game, where you get instant feedback about whether you remember a fact or not. You are able to see immediate progress during your study sessions as you remember more and more of the facts.

Now, when you rate your motivation and focus and record the number of hours spent learning and flashcards covered, you can see that your change in study strategy has dramatically improved your motivation and productivity.

What To Assess?

There are a number of things you can use to measure the reaction to your study strategy. What you measure will be determined by what skills you most need to work on. Keep a journal or tracking table where you record all the outcomes, so you can reflect on them and consider how to improve your learning.

I strongly recommend regularly assessing your knowledge by using practice questions when preparing for written exams. I go into great detail about the power of testing yourself and tracking your learning in later sections.

Practising OSCE skills in front of people and having them mark you is very important when preparing for OSCE exams. You want to find people that give you honest feedback. Sometimes honest feedback can feel painful and hurt your ego, but it is essential if you want to improve. If the people you practise with always tell you how wonderful you are, it is probably worth finding other people that can be a bit blunter. Having a sense of humour can be helpful in making honest constructive feedback easier.

It is worth monitoring how far you are through the content you need to cover, and how many times you have covered that content. If you have 8 weeks to prepare for your exam and 20 topics to cover, and at the end of the first week you have only covered one topic, you need to adapt your strategy so that you are getting through the topics quicker.

If you struggle with motivation, you could monitor your levels of motivation, focus and engagement, similar to the example above.

If you struggle to get the work done, you could monitor how many hours per day and per week you spend revising, then adapt your strategy to increase the number.

I detail the strategy I have used for assessing my strategy in the section on "tracking your learning".

Do Not Be Afraid of Feedback

I recently helped a student prepare to resit his final exams. When talking to him about self-assessment, he explained that the previous time he prepared for his finals he avoided doing practice questions, as he was afraid of what score he would get. He justified avoiding them by telling himself he needed to study more, then he would do questions. He never got around to doing self-assessment questions before his final exams. This meant he had no idea how much he knew or whether his study strategy had been effective.

Assessments can be divided into two categories: formative and summative.

Summative assessments are the ones that decide whether you pass or fail the course. They go on your record and determine your progression. These are the ones that really count.

Formative assessments are designed to provide you with feedback as to how well your learning is going. They do not count towards your final grade and do not determine whether you pass or fail.

There is no reason to be afraid of formative assessments. The only thing you should be afraid of is a lack of formative assessments. Studying without formative assessments is like walking around a spooky house in the dark. Taking regular formative assessments is like turning on the light; suddenly everything seems so much more manageable.

When helping this student prepare for his resits, I advised him to test his knowledge at every opportunity. We caught up on a regular basis to reflect on how his revision was going, further assessing whether his strategy was working. Often this gave him insights that allowed him to adapt and improve his strategy. He went into his exams feeling much more confident and passed without any issues.