The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) published a definition of pain (2020):

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”

It is essential to distinguish between two categories of pain:

- Acute pain – new onset of pain

- Chronic pain – pain present for 3 months or more

Basic Physiology

There are two aspects to the experience of pain:

- Sensory – the sensory signal transmitted from the pain receptor (“it is a sharp sensation, likely a needle”)

- Affective – the unpleasant emotional reaction to the pain (“it is excruciating, I can’t bear it”)

Pain is supposed to indicate underlying or potential damage to tissues, but it can occur without tissue damage. The physiology of pain is very complex. There is still a lot that is not fully understood about the experience of pain.

Pain is subjective, meaning that when someone indicates they are in pain, we need to accept their experience, even when there is no apparent underlying cause.

Pain threshold refers to the point at which sensory input is reported as painful. For example, different temperatures can be applied to the skin to measure the point at which the heat is interpreted as pain. A higher temperature indicates a higher sensory threshold for pain. Allodynia refers to when pain is experienced with sensory inputs that do not normally cause pain (e.g., light touch).

Pain tolerance is different to pain threshold. It is more difficult to define and generally refers to a person’s response to pain. One person may experience pain but think little of it and carry on with their activities as usual. Another person may experience a similar pain and worry that it indicates a serious underlying illness, take time away from work, and seek medical investigations and treatment. Pain tolerance varies massively between individuals and is influenced by many biological, psychological and social factors.

At the most basic level, pain receptors (nociceptors) at the ends of nerves detect damage or potential damage to tissues. Nerve signals are transmitted along the afferent nerves to the spinal cord. Afferent sensory nerves that transmit pain signals are part of the peripheral nervous system and are called primary afferent nociceptors.

Two groups of nerve fibres transmit pain:

- C fibres (unmyelinated and small diameter) – transmit signals slowly and produce dull and diffuse pain sensations

- A-delta fibres (myelinated and larger diameter) – transmit signals fast and produce sharp and localised pain sensations

The signal then travels in the central nervous system, up the spinal cord (mainly in the spinothalamic tract and spinoreticular tract) to the brain where it is interpreted as pain, mainly in the thalamus and cortex.

The main sensory inputs that generate a pain signal are:

- Mechanical (e.g., pressure)

- Heat

- Chemical (e.g., prostaglandins)

However, when directly measuring activity in the peripheral afferent sensory nerves:

- Pain can be experienced without activity in the primary afferent nociceptors

- Activity in the primary afferent nociceptors can be detected without the patient experiencing any pain

Referred pain refers to pain experienced in a location away from the site of tissue damage. For example, patients with a heart attack may have pain in their left arm. There are several possible explanations for referred pain, including:

- Nerves may share the innervation of multiple parts of the body (e.g., the heart and left arm)

- Pain in one area amplifies the sensitivity in the spinal cord to signals coming from other areas

- Activation of the sympathetic nervous system in response to pain results in pain in other areas

Neuropathic pain is caused by abnormal functioning or damage of the sensory nerves, resulting in pain signals being transmitted to the brain.

Measuring Pain

There are no reliable ways to objectively measure the pain someone is experiencing. As it is a subjective experience, pain is measured by asking the patient about their perception of pain.

The visual analogue scale (VAS) involves asking the patient to rate their pain along a horizontal line, where the left end indicates no pain and the right end indicates the worst pain imaginable. The distance along that line can be measured to get a numerical value to represent the pain (e.g., 75mm along a 100mm line).

The numerical rating scale (NRS) involves asking the patient to rate their pain on a numerical scale of 0 – 10, with:

- 0 being no pain at all

- 10 being the worst pain imaginable

Pain can also be rated on a graphical rating scale, with a series of faces going from happy to very unhappy. This may be helpful in children or patients with learning disability.

Analgesic Ladder

The World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic ladder was originally developed to help manage cancer-related pain. It is also often used for acute and chronic painful conditions. The idea is that patients with mild pain start on the first step, and when pain is more severe or does not respond to the lower steps, higher steps on the ladder are used until the pain is adequately managed.

There are three steps to the analgesic ladder:

- Step 1: Non-opioid medications such as paracetamol and NSAIDs

- Step 2: Weak opioids such as codeine and tramadol

- Step 3: Strong opioids such as morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl and buprenorphine

Tramadol has multiple mechanisms of action, including being an SNRI and agonist of opioid receptors.

Other medications may be combined with the analgesic ladder for additional effect (called adjuvants), for example, antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline or duloxetine) or anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin or pregabalin).

Side-Effects

Medication overuse headache is a common side-effect of the long-term use of analgesic medication.

The key side effects of NSAIDs are:

- Gastritis with dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Stomach ulcers

- Exacerbation of asthma

- Hypertension

- Renal impairment

- Coronary artery disease, heart failure and strokes (rarely)

NSAIDs may be inappropriate or contraindicated in patients with:

- Asthma

- Renal impairment

- Heart disease

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Stomach ulcers

Proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole or lansoprazole) are often co-prescribed with NSAIDs to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., acid reflux, gastritis and stomach ulcers).

The key side effects of opioids are:

- Constipation

- Skin itching (pruritus)

- Nausea

- Altered mental state (sedation, cognitive impairment or confusion)

- Respiratory depression (usually only with larger doses in opioid-naive patients)

Naloxone is used to reverse the effects of opioids in life-threatening overdose (usually due to respiratory depression).

Opioids in Palliative Care

Using opioids to control pain in palliative patients is a specific scenario where the doses are titrated and optimised over time. This involves using a combination of:

- Background opioids (e.g., 12-hourly modified-release oral morphine)

- Rescue doses for breakthrough pain (e.g., immediate-release oral morphine solution)

The rescue dose is usually 1/6 of the background 24-hour dose. For example, with a background of 30mg over 24 hours of morphine (e.g., 15mg every 12 hours), each rescue dose will be 5mg, given every 2-4 hours as required.

If the patient requires regular rescue doses for breakthrough pain, the dose of the background opioid can be increased. The rescue doses must also increase to 1/6 of the background 24-hour dose.

TOM TIP: Remember that each rescue dose is 1/6 of the 24-hour background dose. Exam questions might ask something like, “this patient is on 30mg of modified-release morphine every 12 hours; what would be the correct breakthrough dose?” In this scenario, 10mg is the correct answer, as the patient is getting 60mg background morphine every 24 hours (30mg twice a day).

Opioid Conversion

The information here is from the BNF, which gives approximate conversions between different opiates, equivalent to 10mg of oral morphine. The conversions are not exact, and patients can respond differently to various opioids.

|

Opioid |

Route |

Equivalent Dose |

|

Morphine |

Oral |

10mg |

|

Codeine |

Oral |

100mg |

|

Tramadol |

Oral |

100mg |

|

Oxycodone |

Oral |

6.6mg |

|

Morphine |

IV / IM / SC |

5mg |

|

Diamorphine |

IV / IM / SC |

3mg |

It is also possible to use opioid patches for background analgesia:

- Buprenorphine patches (5 mcg/hour patches are roughly equivalent to 12 mg/24 hours of oral morphine)

- Fentanyl patches (12 mcg/hour patches are roughly equivalent to 30mg/24 hours of oral morphine)

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain refers to pain that has been present or reoccurs in one or more areas over more than three months. Up to 50% of the adults in the UK are affected by chronic pain.

The NICE guidelines on chronic pain (April 2021) separates chronic pain into:

- Chronic primary pain – where no underlying condition can adequately explain the pain

- Chronic secondary pain – where an underlying condition can explain the pain (e.g., arthritis)

Biological, psychological and social factors contribute to the persistence and severity of pain. Physical processes that can lead to chronic pain include:

- Sensitisation of the primary afferent nociceptors by frequent stimulation

- Increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system

- Increased muscle contraction in response to pain

Chronic pain is a complex condition that can be challenging to manage. It often fluctuates, with flare-ups, and may get worse over time. Good communication and building a relationship is important. Part of management aims to maintain the quality of life despite the pain.

Options for managing chronic primary pain in the NICE guidelines (2021) include:

- Supervised group exercise programs

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

- Acupuncture

- Antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, duloxetine or an SSRI)

The NICE guidelines (2021) specifically state that for chronic primary pain, patients should not be started on:

- Paracetamol

- NSAIDs

- Opiates

- Anti-epileptic drugs (e.g., pregabalin or gabapentin)

In chronic secondary pain, analgesia may be helpful depending on the underlying cause. For example, in patients with osteoarthritis, the pain may be managed with NSAIDs.

TOM TIP: It is worth remembering the NICE guidelines (2021) clearly state to avoid essentially all forms of analgesia in chronic primary pain, except antidepressants.

Neuropathic Pain

Typical features of neuropathic pain are numbness, burning, tingling, pins and needles or an electric shock sensation. Common causes of neuropathic pain include:

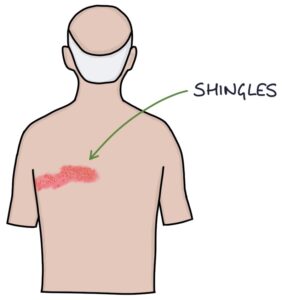

- Post-herpetic neuralgia from shingles is in the distribution of a dermatome and usually on the trunk

- Nerve damage from surgery

- Multiple sclerosis

- Diabetic neuralgia (typically affecting the feet)

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Complex regional pain syndrome

The DN4 questionnaire can be used to assess the characteristics of the pain and the likelihood of neuropathic pain. Patients are scored out of 10. A score of 4 or more indicates neuropathic pain.

There are four first-line treatments for neuropathic pain:

- Amitriptyline – a tricyclic antidepressant

- Duloxetine – an SNRI antidepressant

- Gabapentin – an anticonvulsant

- Pregabalin – an anticonvulsant

Only one neuropathic medication is used at a time. Tramadol may be used only as a short-term rescue for flares.

NICE CKS (2022) recommend carbamazepine as the first-line medication for trigeminal neuralgia.

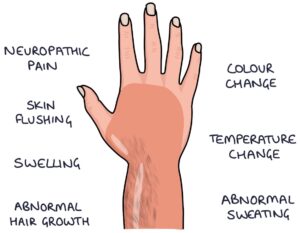

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterised by areas of abnormal nerve functioning, causing neuropathic pain, abnormal sensations and skin changes. It is often triggered by an injury and isolated to one limb.

The area can become hypersensitive, with pain associated with normal sensations (allodynia). There may be intermittent swelling, colour changes, temperature changes, skin flushing and abnormal sweating.

Treatment is guided by a pain specialist and is similar to other types of neuropathic pain.

Last updated October 2023