Bowel cancer is the fourth most prevalent cancer in the UK, behind breast, prostate and lung cancer. Bowel cancer usually refers to cancer of the colon or rectum. Small bowel and anal cancers are less common.

Risk Factors

There are a number of factors that increase the risk of colorectal cancer:

- Family history of bowel cancer

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch syndrome

- Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis)

- Increased age

- Diet (high in red and processed meat and low in fibre)

- Obesity and sedentary lifestyle

- Smoking

- Alcohol

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant condition involving malfunctioning of the tumour suppressor genes called adenomatous polyposis coli (APC). It results in many polyps (adenomas) developing along the large intestine. These polyps have the potential to become cancerous (usually before the age of 40). Patients have their entire large intestine removed prophylactically to prevent the development of bowel cancer (panproctocolectomy).

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is also known as Lynch syndrome. It is an autosomal dominant condition that results from mutations in DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes. Patients are at a higher risk of a number of cancers, but particularly colorectal cancer. Unlikely FAP, it does not cause adenomas and tumours develop in isolation.

Presentation

The red flags that should make you consider bowel cancer are:

- Change in bowel habit (usually to more loose and frequent stools)

- Unexplained weight loss

- Rectal bleeding

- Unexplained abdominal pain

- Iron deficiency anaemia (microcytic anaemia with low ferritin)

- Abdominal or rectal mass on examination

The NICE guidelines for suspected cancer recognition and referral (updated January 2021) give various criteria for a “two week wait” urgent cancer referral, depending on the patient’s age and combination of symptoms. For example:

- Over 40 years with abdominal pain and unexplained weight loss

- Over 50 years with unexplained rectal bleeding

- Over 60 years with a change in bowel habit or iron deficiency anaemia

Patients may present acutely with obstruction if the tumour blocks the passage through the bowel. This presents a surgical emergency with vomiting, abdominal pain and absolute constipation.

TOM TIP: Iron deficiency anaemia on its own without any other explanation (i.e. heavy menstruation) is an indication for a “two week wait” cancer referral for colonoscopy and gastroscopy (“top and tail”) for GI malignancy. This is because GI malignancies such as bowel cancer can cause microscopic bleeding (not visible in bowel movements) that eventually lead to iron deficiency anaemia.

Faecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) and Bower Cancer Screening

Faecal immunochemical tests (FIT) look very specifically for the amount of human haemoglobin in the stool. FIT replaced the older stool test called the faecal occult blood (FOB) test, which detected blood in the stool but could give false positives by detecting blood in food (e.g., from red meats).

FIT tests can be used as a test in general practice to help assess for bowel cancer in specific patients who do not meet the criteria for a two week wait referral, for example:

- Over 50 with unexplained weight loss and no other symptoms

- Under 60 with a change in bowel habit

FIT tests are used for the bowel cancer screening program in England. In England, people aged 60 – 74 years are sent a home FIT test to do every 2 years. If the results come back positive they are sent for a colonoscopy.

People with risk factors such as FAP, HNPCC or inflammatory bowel disease are offered a colonoscopy at regular intervals to screen for bowel cancer.

Investigations

Colonoscopy is the gold standard investigation. It involves an endoscopy to visualise the entire large bowel. Any suspicious lesions can be biopsied to get a histological diagnosis, or tattoo in preparation for surgery.

Sigmoidoscopy involves an endoscopy of the rectum and sigmoid colon only. This may be used in cases where the only feature is rectal bleeding. There is the obvious risk of missing cancers in other parts of the colon.

CT colonography is a CT scan with bowel prep and contrast to visualise the colon in more detail. This may be considered in patients less fit for a colonoscopy but it is less detailed and does not allow for a biopsy.

Staging CT scan involves a full CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis (CT TAP). This is used to look for metastasis and other cancers. It may be used after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, or as part of the initial workup in patients with vague symptoms (e.g., weight loss) in addition to colonoscopy as an initial investigation to exclude other cancers.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a tumour marker blood test for bowel cancer. This is not helpful in screening, but it may be used for predicting relapse in patients previously treated for bowel cancer.

Dukes’ Classification

Dukes’ classification is the system previously used for bowel cancer. It has now been replaced in clinical practice by the TNM classification, but you may come across it in older textbooks or question banks. A brief summary is:

- Dukes A – confined to mucosa and part of the muscle of the bowel wall

- Dukes B – extending through the muscle of the bowel wall

- Dukes C – lymph node involvement

- Dukes D – metastatic disease

TNM classification

T for Tumour:

- TX – unable to assess size

- T1 – submucosa involvement

- T2 – involvement of muscularis propria (muscle layer)

- T3 – involvement of the subserosa and serosa (outer layer), but not through the serosa

- T4 – spread through the serosa (4a) reaching other tissues or organs (4b)

N for Nodes:

- NX – unable to assess nodes

- N0 – no nodal spread

- N1 – spread to 1-3 nodes

- N2 – spread to more than 3 nodes

M for Metastasis:

- M0 – no metastasis

- M1 – metastasis

Management

After a patient has a diagnosis, they are discussed at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. The colorectal MDT involves surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, histopathologists, specialist nurses and other health professionals to agree on the most appropriate management options.

The choice of management depends on many factors:

- Clinical condition

- General health

- Stage

- Histology

- Patient wishes

Options for managing bowel cancer (in any combination) are:

- Surgical resection

- Chemotherapy

- Radiotherapy

- Palliative care

Surgical Resection

The ideal scenario with bowel cancer is to surgically remove the entire tumour. Removal of the section of bowel affected by the tumour can be potentially curative. Surgery can also be used palliatively, to reduce the size of the tumour and improve symptoms.

Laparoscopic surgery (where possible) generally gives better recovery and fewer complications compared with open surgery. Robotic surgery is increasingly being used, which is essentially a more advanced laparoscopic procedure.

Surgery involves:

- Identifying the tumour (it may have been tattooed during an endoscopy)

- Removing the section of bowel containing the tumour,

- Creating an end-to-end anastomosis (sewing the remaining ends back together)

- Alternatively creating a stoma (bringing the open section of bowel onto the skin)

Operations

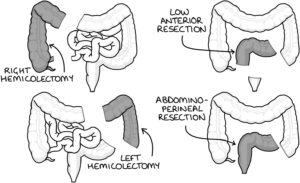

Right hemicolectomy involves removal of the caecum, ascending and proximal transverse colon.

Left hemicolectomy involves removal of the distal transverse and descending colon.

High anterior resection involves removing the sigmoid colon (may be called a sigmoid colectomy).

Low anterior resection involves removing the sigmoid colon and upper rectum but sparing the lower rectum and anus.

Abdomino-perineal resection (APR) involves removing the rectum and anus (plus or minus the sigmoid colon) and suturing over the anus. It leaves the patient with a permanent colostomy.

Hartmann’s procedure is usually an emergency procedure that involves the removal of the rectosigmoid colon and creation of an colostomy. The rectal stump is sutured closed. The colostomy may be permanent or reversed at a later date. Common indications are acute obstruction by a tumour, or significant diverticular disease.

Complications

There is a long list of potential complications of surgery for bowel cancer:

- Bleeding, infection and pain

- Damage to nerves, bladder, ureter or bowel

- Post-operative ileus

- Anaesthetic risks

- Laparoscopic surgery converted during the operation to open surgery (laparotomy)

- Leakage or failure of the anastomosis

- Requirement for a stoma

- Failure to remove the tumour

- Change in bowel habit

- Venous thromboembolism (DVT and PE)

- Incisional hernias

- Intra-abdominal adhesions

Low Anterior Resection Syndrome

Low anterior resection syndrome may occur after resection of a portion of bowel from the rectum, with anastomosis between the colon and rectum. It can result in a number of symptoms, including:

- Urgency and frequency of bowel movements

- Faecal incontinence

- Difficulty controlling flatulence

Follow-Up

Patients will be followed up for a period of time (e.g., 3 years) following curative surgery. This includes:

- Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- CT thorax, abdomen and pelvis

Last updated May 2021