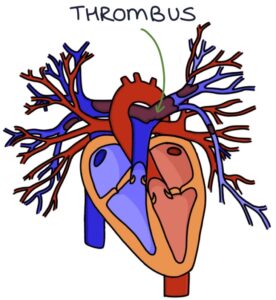

Pulmonary embolism (PE) describes a blood clot (thrombus) in the pulmonary arteries. An embolus is a thrombus that has travelled in the blood, often from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in a leg. The thrombus will block the blood flow to the lung tissue and strain the right side of the heart. DVTs and PEs are collectively known as venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Risk Factors

Several factors can put patients at higher risk of developing a DVT or PE. In many of these situations (e.g., surgery), prophylactic treatment is used to reduce the risk of VTE.

- Immobility

- Recent surgery

- Long-haul travel

- Pregnancy

- Hormone therapy with oestrogen (e.g., combined oral contraceptive pill or hormone replacement therapy)

- Malignancy

- Polycythaemia (raised haemoglobin)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Thrombophilia

TOM TIP: In your exams, when a patient presents with possible features of a DVT or PE, ask about risk factors such as periods of immobility, surgery and long-haul flights to score extra points.

VTE Prophylaxis

Every patient admitted to hospital is assessed for their risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Higher-risk patients receive prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin) unless contraindicated. Contraindications include active bleeding or existing anticoagulation with warfarin or a DOAC.

Anti-embolic compression stockings are also used unless contraindicated (e.g., peripheral arterial disease).

Presentation

Pulmonary embolism can be asymptomatic (discovered incidentally), present with subtle signs and symptoms, or even cause sudden death. A low threshold for suspecting a PE is required. Presenting features include:

- Shortness of breath

- Cough

- Haemoptysis (coughing up blood)

- Pleuritic chest pain (sharp pain on inspiration)

- Hypoxia

- Tachycardia

- Raised respiratory rate

- Low-grade fever

- Haemodynamic instability causing hypotension

There may also be signs and symptoms of a deep vein thrombosis, such as unilateral leg swelling and tenderness.

PERC Rule

The pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) are recommended by the NICE guidelines (2020) when the clinician estimates less than a 15% probability of a pulmonary embolism to decide whether further investigations for a PE are needed. If all the criteria are met, further investigations for a PE are not required.

Wells Score

The Wells score predicts the probability of a patient having a PE. It is used when PE is suspected. It accounts for risk factors (e.g., recent surgery) and clinical findings (e.g., heart rate above 100 and haemoptysis).

Diagnosis

A chest x-ray is usually normal in a pulmonary embolism but is required to rule out other pathology.

The Wells score is used when considering pulmonary embolism. The outcome decides the next step:

- Likely: perform a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) or alternative imaging (see below)

- Unlikely: perform a d-dimer, and if positive, perform a CTPA

D-dimer is a sensitive (95%) but not a specific blood test for VTE. It helps exclude VTE where there is a low suspicion. It is almost always raised if there is a DVT. However, other conditions can cause a raised d-dimer:

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Heart failure

- Surgery

- Pregnancy

There are three imaging options for establishing a diagnosis of a pulmonary embolism:

- CT pulmonary angiogram (the usual first-line)

- Ventilation-perfusion single photon emission computed tomography (V/Q SPECT) scan

- Planar ventilation–perfusion (VQ) scan

CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) is a chest CT scan with an intravenous contrast that highlights the pulmonary arteries to demonstrate any blood clots. This is the first-line imaging for pulmonary embolism, as it is readily available, provides a more definitive assessment and gives information about alternative diagnoses, such as pneumonia or malignancy.

Ventilation-perfusion (VQ) scan involves using radioactive isotopes and a gamma camera to compare ventilation with the perfusion of the lungs. They are used in patients with renal impairment, contrast allergy or at risk from radiation, where a CTPA is unsuitable. First, the isotopes are inhaled to fill the lungs, and a picture is taken to demonstrate ventilation. Next, a contrast containing isotopes is injected, and a picture is taken to illustrate perfusion. The two images are compared. With a pulmonary embolism, there will be a deficit in perfusion as the thrombus blocks blood flow to the lung tissue. The lung tissue will be ventilated but not perfused. Planar V/Q scans produce 2D images. V/Q SPECT scans produce 3D images, making them more accurate.

TOM TIP: Patients with a pulmonary embolism often have respiratory alkalosis on an ABG. Hypoxia causes a raised respiratory rate. Breathing fast means they “blow off” extra CO2. A low CO2 means the blood becomes alkalotic. The other main cause of respiratory alkalosis is hyperventilation syndrome. Patients with PE will have a low pO2, whereas patients with hyperventilation syndrome will have a high pO2.

Management

Supportive management depends on the severity of symptoms and the clinical presentation, including:

- Admission to hospital if required

- Oxygen as required

- Analgesia if required

- Monitoring for any deterioration

Anticoagulation is the mainstay of management. In most patients, NICE (2020) recommend treatment-dose apixaban or rivaroxaban as first-line. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the main alternative. This should be started immediately in patients where PE is suspected and there is a delay in getting a scan to confirm the diagnosis.

Massive PE with haemodynamic compromise is treated with a continuous infusion of unfractionated heparin and considering thrombolysis. Thrombolysis involves injecting a fibrinolytic (breaks down fibrin) medication that rapidly dissolves clots. There is a significant risk of bleeding with thrombolysis, making it dangerous. It is only used in patients with a massive PE where the benefits outweigh the risks. Some examples of thrombolytic agents are streptokinase, alteplase and tenecteplase.

There are two ways thrombolysis can be performed:

- Intravenously using a peripheral cannula

- Catheter-directed thrombolysis (directly into the pulmonary arteries using a central catheter)

Long-Term Anticoagulation

The options for long-term anticoagulation in VTE are a DOAC, warfarin or LMWH.

Direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are oral anticoagulants that do not require monitoring. Options are apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban and dabigatran. They are suitable for most patients. Exceptions include severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance less than 15 ml/min), antiphospholipid syndrome and pregnancy.

Warfarin is a vitamin K antagonist. The target INR for warfarin is between 2 and 3 when treating DVTs and PEs. It is the first-line in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (who also require initial concurrent treatment with LMWH).

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the first-line anticoagulant in pregnancy.

Continue anticoagulation for:

- 3 months with a reversible cause (then review)

- Beyond 3 months with unprovoked PE, recurrent VTE or an irreversible underlying cause (e.g., thrombophilia)

- 3-6 months in active cancer (then review)

Last updated June 2023