Dialysis is a method for performing the filtration tasks of the kidneys artificially. It is used in patients with end-stage renal failure or complications of acute kidney injury. It involves removing excess fluid, solutes and waste products.

Indications

The “AEIOU” mnemonic can be used for the indications for short-term dialysis:

- A – Acidosis (severe and not responding to treatment)

- E – Electrolyte abnormalities (particularly treatment-resistant hyperkalaemia)

- I – Intoxication (overdose of certain medications)

- O – Oedema (severe and unresponsive pulmonary oedema)

- U – Uraemia symptoms such as seizures or reduced consciousness

End-stage renal failure (CKD stage 5) is the main indication for long-term dialysis.

Long-Term Dialysis

There are two options for dialysis in patients requiring it long-term:

- Haemodialysis

- Peritoneal dialysis

The decision about which form to use is based on individual factors, such as preference, lifestyle and co-morbidities.

Haemodialysis

With haemodialysis, patients have their blood filtered by a haemodialysis machine. Regimes can vary, but a typical regime might be 4 hours a day, three days per week.

Blood is taken out of the body, passed through the dialysis machine, and pumped back into the body. The blood passes along a series of semipermeable membranes inside the dialysis machine. Solutes filter out of the blood, across the membrane and into a fluid called dialysate. The concentration gradient between the blood and the dialysate fluid causes water and solutes to diffuse out of the blood and across the membrane. Anticoagulation with citrate or heparin is necessary to prevent blood clotting in the machine and during the process.

Haemodialysis requires good access to an abundant blood supply. Two tubes are needed, one to remove the blood and one to put the blood back in. The options for longer-term access are:

- Tunnelled cuffed catheter

- Arteriovenous fistula

Tunnelled Cuffed Catheter

A tunnelled cuffed catheter is a tube inserted into the subclavian or jugular vein with a tip in the superior vena cava or right atrium. It has two lumens, one for blood exiting the body (usually red) and one for blood entering the body (usually blue). They can stay long-term and be used for regular haemodialysis.

A Dacron cuff surrounds the catheter. The cuff promotes healing and adhesion of tissue, making the catheter more permanent and providing a barrier to infection.

The main complications are infection and blood clots within the catheter.

Arteriovenous Fistula

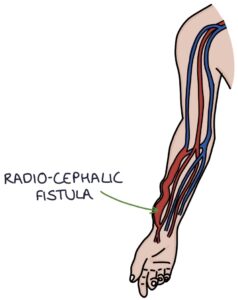

An AV fistula is an artificial connection between an artery and a vein. It bypasses the capillary system and allows blood to flow under high pressure from the artery directly into the vein. This provides a permanent, large, easy-access blood vessel with high-pressure arterial blood flow. Creating an A-V fistula requires a surgical operation and a maturation period of 4-16 weeks before it can be used.

The options are:

- Radiocephalic fistula at the wrist (radial artery to cephalic vein)

- Brachiocephalic fistula at the antecubital fossa (brachial artery to cephalic vein)

- Brachiobasilic fistula at the upper arm (less common and a more complex operation)

AV fistula features to examine in an OSCE are:

- Skin integrity

- Aneurysms

- Palpable thrill (a fine vibration felt over the anastomosis)

- A “machinery murmur” on auscultation over the fistula

Complications of AV fistula include:

- Aneurysm

- Infection

- Thrombosis

- Stenosis

- STEAL syndrome

- High-output heart failure

STEAL syndrome occurs when there is inadequate blood flow to the limb distal to the fistula. The AV fistula “steals” blood from the rest of the limb. Blood is diverted away from the part of the limb it was supposed to supply, leading to ischaemia. Instead, it flows through the fistula and into the venous system.

High-output heart failure is caused by blood flowing quickly from the arterial to the venous system through an A-V fistula. There is a rapid return of blood to the heart, increasing the pre-load (how full the heart is before it pumps). This leads to hypertrophy of the heart muscle and heart failure.

TOM TIP: NEVER take blood from a fistula! This is a lifeline for the patient, providing dialysis access. If it gets damaged, it will set them back massively.

Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis uses the peritoneal membrane to filter the blood. A special dialysis solution containing dextrose is added to the peritoneal cavity. Ultrafiltration occurs from the blood, across the peritoneal membrane, into the dialysis solution. The dialysis solution is replaced, taking away the waste products that have filtered out of the blood.

Peritoneal dialysis involves a Tenckhoff catheter. This plastic tube is inserted into the peritoneal cavity, with one end on the outside, allowing access to the peritoneal cavity to insert and remove the dialysis solution.

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is where dialysis solution is always in the peritoneal cavity. There are various regimes for changing the solution. For example, two litres of solution replaced four times daily.

Automated dialysis is the alternative. A machine continuously replaces the dialysis fluid for 8-10 hours overnight.

Complications of peritoneal dialysis include:

- Bacterial peritonitis (infections in the high-sugar environment are common and serious)

- Peritoneal sclerosis (thickening and scarring of the peritoneal membrane)

- Ultrafiltration failure (the dextrose is absorbed, reducing the filtration gradient, making ultrafiltration less effective)

- Weight gain (due to absorption of the dextrose)

- Psychosocial implications

Last updated September 2023