Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and progressive autoimmune condition involving demyelination in the central nervous system. The immune system attacks the myelin sheath of the myelinated neurones.

Multiple sclerosis typically presents in young adults (under 50 years) and is more common in women.

Pathophysiology

Myelin covers the axons of neurones and helps electrical impulses travel faster. Myelin is provided by cells that wrap themselves around the axons:

- Oligodendrocytes in the central nervous system

- Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system

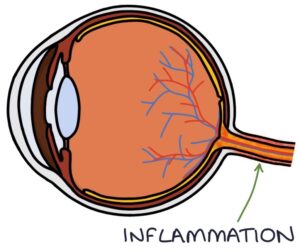

Multiple sclerosis affects the central nervous system (the oligodendrocytes). Inflammation and immune cell infiltration cause damage to the myelin, affecting the electrical signals moving along the neurones.

When a patient presents with symptoms of an MS attack (e.g., an episode of optic neuritis), there are often other demyelinating lesions throughout the central nervous system, most of which are not causing symptoms.

In early disease, re-myelination can occur, and the symptoms can resolve. In the later stages of the disease, re-myelination is incomplete, and the symptoms gradually become more permanent.

A characteristic feature of MS is that lesions vary in location, meaning that the affected sites and symptoms change over time. The lesions are described as “disseminated in time and space”.

Causes

The cause of the multiple sclerosis is unclear, but there is growing evidence that it may be influenced by:

- Multiple genes

- Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

- Low vitamin D

- Smoking

- Obesity

Onset

Symptoms usually progress over more than 24 hours. Symptoms tend to last days to weeks at the first presentation and then improve. There are many ways MS can present, depending on the location of the lesions.

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis is the most common presentation of multiple sclerosis. It involves demyelination of the optic nerve and presents with unilateral reduced vision, developing over hours to days.

Key features are:

- Central scotoma (an enlarged central blind spot)

- Pain with eye movement

- Impaired colour vision

- Relative afferent pupillary defect

A relative afferent pupillary defect is where the pupil in the affected eye constricts more when shining a light in the contralateral eye than when shining it in the affected eye. When testing the direct pupillary reflex, there is a reduced pupil response to shining light in the eye affected by optic neuritis. However, the affected eye has a normal pupil response when testing the consensual pupillary reflex.

Other causes of optic neuritis include:

- Sarcoidosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Syphilis

- Measles or mumps

- Neuromyelitis optica

- Lyme disease

Patients presenting with acute loss of vision need urgent ophthalmology input. Optic neuritis is treated with high-dose steroids. Changes on an MRI scan help to predict which patients will go on to develop MS.

Eye Movement Abnormalities

Lesions affecting the oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV) or abducens (CN VI) can cause double vision (diplopia) and nystagmus. Oscillopsia refers to the visual sensation of the environment moving and being unable to create a stable image.

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is caused by a lesion in the medial longitudinal fasciculus. The nerve fibres of the medial longitudinal fasciculus connect the cranial nerve nuclei (“internuclear”) that control eye movements (the 3rd, 4th and 6th cranial nerve nuclei). These fibres are responsible for coordinating the eye movements to ensure the eyes move together. It causes impaired adduction on the same side as the lesion (the ipsilateral eye) and nystagmus in the contralateral abducting eye.

A lesion in the abducens (CN VI) causes a conjugate lateral gaze disorder. Conjugate means connected. Lateral gaze is where both eyes move to look laterally to the left or right. When looking laterally in the direction of the affected eye, the affected eye will not be able to abduct. For example, in a lesion involving the left eye, when looking to the left, the right eye will adduct (move towards the nose), and the left eye will remain in the middle.

Focal Neurological Symptoms

Multiple sclerosis may present with focal weakness, for example:

- Incontinence

- Horner syndrome

- Facial nerve palsy

- Limb paralysis

Multiple sclerosis may present with focal sensory symptoms, for example:

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Numbness

- Paraesthesia (pins and needles)

- Lhermitte’s sign

Lhermitte’s sign describes an electric shock sensation that travels down the spine and into the limbs when flexing the neck. It indicates disease in the cervical spinal cord in the dorsal column. It is caused by stretching the demyelinated dorsal column.

Transverse myelitis refers to a site of inflammation in the spinal cord, which results in sensory and motor symptoms depending on the location of the lesion.

Ataxia

Ataxia is a problem with coordinated movement. It can be sensory or cerebellar.

Sensory ataxia is due to loss of proprioception, which is the ability to sense the position of the joint (e.g., is the joint flexed or extended). This results in a positive Romberg’s test (they lose balance when standing with their eyes closed) and can cause pseudoathetosis (involuntary writhing movements). A lesion in the dorsal columns of the spine can cause sensory ataxia.

Cerebellar ataxia results from problems with the cerebellum coordinating movement, indicating a cerebellar lesion.

Disease Patterns

The disease course is highly variable between individuals. Some patients have mild relapsing-remitting episodes for life, while others have symptoms that progress without any improvement. There are classifications used to describe the patterns, which are not separate conditions but part of a spectrum of disease activity.

Clinically isolated syndrome describes the first episode of demyelination and neurological signs and symptoms. Patients with clinically isolated syndrome may never have another episode or may go on to develop MS. Lesions on an MRI scan suggest they are more likely to progress to MS.

Relapsing-remitting MS is the most common pattern when first diagnosed. It is characterised by episodes of disease and neurological symptoms followed by recovery. The symptoms tend to occur in different areas with each episode. It can be further classified based on whether the disease is active or worsening:

- Active: new symptoms are developing, or new lesions are appearing on the MRI

- Not active: no new symptoms or MRI lesions are developing

- Worsening: there is an overall worsening of disability over time

- Not worsening: there is no worsening of disability over time

Secondary progressive MS is where there was relapsing-remitting disease, but now there is a progressive worsening of symptoms with incomplete remissions. Symptoms become increasingly permanent. Secondary progressive MS can be further classified based on whether the disease is active or progressing.

Primary progressive MS involves worsening disease and neurological symptoms from the point of diagnosis without relapses and remissions. This can be further classified based on whether it is active or progressing.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by a neurologist based on the clinical picture and symptoms suggesting lesions that change location over time. Other causes for the symptoms need to be excluded.

Investigations can support the diagnosis:

- MRI scans can demonstrate typical lesions

- Lumbar puncture can detect oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

Management

A specialist multidisciplinary team (MDT) manages multiple sclerosis, including neurologists, specialist nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Disease-modifying therapies aim to induce long-term remission with no disease activity. Many options target various aspects of the immune system to reduce relapses and disease progression.

Relapses may be treated with steroids. The NICE guidelines (2022) suggest either:

- 500mg orally daily for 5 days

- 1g intravenously daily for 3–5 days (where oral treatment has previously failed or where relapses are severe)

Symptomatic treatments include:

- Exercise to maintain activity and strength

- Fatigue may be managed with amantadine, modafinil or SSRIs

- Neuropathic pain may be managed with medication (e.g., amitriptyline or gabapentin)

- Depression may be managed with antidepressants, such as SSRIs

- Urge incontinence may be managed with antimuscarinic medications (e.g., solifenacin)

- Spasticity may be managed with baclofen or gabapentin

- Oscillopsia may be managed with gabapentin or memantine

Last updated September 2023